On a chilly Thursday afternoon in early March, leaders in the Rochester arts community gathered in the Wilder Room on East Avenue.

They had been invited there by the city’s foremost cheerleader of downtown, Heidi Zimmer-Meyer, the longtime president of the Rochester Downtown Development Corp., a nonprofit whose mission is to attract investment in the corridor.

She wanted to talk about a vision she and city officials shared for creating something called a “business improvement district” downtown, and ask for their ideas and support for a plan to help kick it off. That plan included a call for artists to paint storefront windows to “enhance the vibrancy” of the neighborhood.

The news did not go over well with the room.

Artists wondered whether she was aware of their existing efforts to create a lively downtown. They scoffed at the idea of an economic development agency coordinating art calls. They questioned why, if there was money to spend on art, it wasn’t being turned over to arts organizations, whose lack of public funding is well documented.

Within weeks, many of the artists there would dismiss the plan as literal window dressing intended to push through a concept that they argued could potentially drive artists out of the neighborhood they were being asked to “enhance.”

Today, their distrust of what they see as overreach by economic development and business interests has morphed into an all-out campaign to undercut the entire effort to establish a business improvement district downtown.

Today, their distrust of what they see as overreach by economic development and business interests has morphed into an all-out campaign to undercut the entire effort to establish a business improvement district downtown.

Artists have launched an offensive in the form of protests, social media campaigns, and a website called nobidroc.com — as in “no business improvement district” in Rochester. More than 650 people and counting have signed a related online petition.

When supporters began marketing their efforts with the tagline “Downtown Definitely,” the artists turned the motto on its head with their own version: “Downtown Dubiously.”

“They seem to want arts and culture to factor heavily into their plans, yet there was no transparent process or meaningful art community input,” said Bleu Cease, the executive director of the Rochester Contemporary Art Center on East Avenue and a leader in the movement to stop a business improvement district.

The arts community’s protestations gathered enough steam in July to force Mayor Malik Evans and the City Council to postpone a vote on the matter.

The arts community’s protestations gathered enough steam in July to force Mayor Malik Evans and the City Council to postpone a vote on the matter.

The vote was to formally begin a planning process to get the district up and running by 2024. Officials said they wanted time to clarify and answer myriad concerns that critics have raised. They might try again for a vote in August.

“People are thinking already, ‘Oh, this is a done deal,’” Evans said. “This is the beginning phases. This is not a fait accompli.”

Supporters of the proposed business improvement district say opponents are fearmongering and have it wrong.

The goal, they insist, is double-barreled: activate street vitality and enhance promotional efforts to bring people downtown and to other spaces that the city, the state, and private investors have sunk hundreds of millions of dollars into rehabbing.

“We’ve been hearing complaints for years about how dead downtown streets are,” said Zimmer-Meyer, who retired in June.

THE BONES OF A ‘BID’

THE BONES OF A ‘BID’

Business improvements districts, known as BIDs, are public-private partnerships.

Property owners in a defined area agree to pay additional taxes for services and quality-of-life improvements that the local government may be unable or unwilling to provide.

These can be things like special events, lighting, sanitation, marketing, beautification, public art, hospitality, and security services.

These districts began popping up in the United States in the mid-1970s, and cities across the country began embracing them ever since they were credited with helping transform Times Square and Union Square in New York City from dens of seediness to thriving tourist destinations. Today there are more than 1,200 BIDs nationwide.

Rochester created one in High Falls in 2005 without controversy. But a muddled attempt at organizing a downtown BID collapsed a decade ago.

The catalyst for the latest push was the realization of a series of state- and city-funded public works projects along the Genesee River downtown and East Main Street.

Some $5 million has been set aside to create an entity to manage and promote those efforts, most of that in taxpayer money in the form of a state grant. The rest consists of $1 million in private donations, mostly from downtown business and property owners, and revenue from the Rochester Downtown Development Corp., which is primarily funded by corporations, institutions, and real estate companies.

“We need better organization, coordination on all of these redevelopment efforts and promotional efforts,” said Vinnie Esposito, who oversees New York state’s regional economic development efforts, specifically in the Finger Lakes, and supports the concept of a downtown BID.

“It’s not good enough just to improve a park and a trail and a public space,” he said. “What we really need to do is then promote and activate, and make those spaces come alive.”

Many in the arts community, however, argue that downtown is already alive and thriving organically through the work of artists and everyday people who make their homes and livings there.

Many in the arts community, however, argue that downtown is already alive and thriving organically through the work of artists and everyday people who make their homes and livings there.

Their opposition hews closely to that of critics of BIDs elsewhere who say the districts serve the interests of real estate developers by providing them the means to impose an unnecessary tax that could be passed along to tenants in the form of higher rents. They call them “classist” and “undemocratic,” and argue they lead to gentrification.

Opponents in Rochester have gone so far as to classify the proposed district as “21st century redlining.”

Chief among their concerns is that BIDs, which by state law are overseen by a board of directors made up primarily of property owners, could ultimately control access to public spaces and spend the taxes they assess without the typical public checks and balances. In essence, they say, BIDs operate as a shadow government.

Chief among their concerns is that BIDs, which by state law are overseen by a board of directors made up primarily of property owners, could ultimately control access to public spaces and spend the taxes they assess without the typical public checks and balances. In essence, they say, BIDs operate as a shadow government.

“Do we want to turn downtown Rochester into a privatized oasis of phony vitality?” asked Kelly Cheatle, a vocal opponent who is the artistic director at Airigami, a company on State Street near Lyell Avenue that creates intricate balloon arrangements for local and national clients.

“Do we want to give wealthy developers the power to hire private security to secure their vision of a ‘vital’ downtown?” Cheatle asked. “Do we want a secretive board to be able to levy taxes without public scrutiny? No.”

SHADOW GOVERNMENT OR ECONOMIC ENGINE?

Business improvement districts vary in size and scope, and must be authorized through a multistep process that officials here say will take two years or more and requires buy-in from a majority of property owners in the designated area.

That process includes, among other things, devising a map of the district, proposing an annual budget, outlining how much property owners will pay, and public hearings on the matter. None of those things has happened yet.

That has not stopped opponents, though, from pushing the narrative that BIDs are secret societies, accountable to no one.

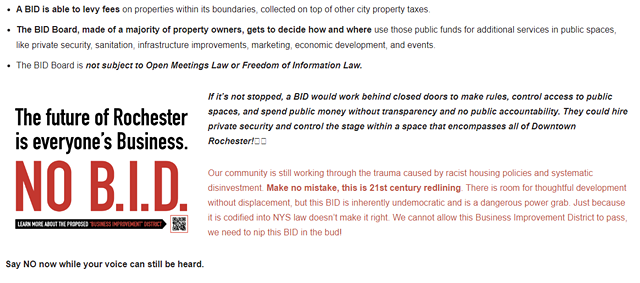

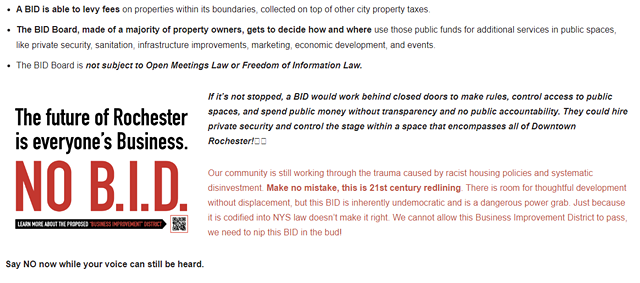

“If it’s not stopped,” reads the introduction at nobidroc.com, “a BID would work behind closed doors to make rules, control access to public spaces, and spend public money without transparency and no public accountability.”

But the state Committee on Open Government has determined that BIDs are “public bodies” subject to the state’s Open Meetings Law and the Freedom of Information Law. That ruling, made in 2016, was a reversal of previous legal opinions that held that open meetings and records laws were not applicable to business improvement districts.

But the state Committee on Open Government has determined that BIDs are “public bodies” subject to the state’s Open Meetings Law and the Freedom of Information Law. That ruling, made in 2016, was a reversal of previous legal opinions that held that open meetings and records laws were not applicable to business improvement districts.

The Evans administration backed that interpretation in correspondence with the City Council recently. The administration also noted that the city can impose a lifespan on the existence of a BID and force one to shut down.

State law also requires BIDs in cities like Rochester to include three members on their boards who are appointed respectively by the mayor, the chief financial officer, and the City Council. Opponents here have dismissed those posts as “token” representation.

To some degree, these districts function as an extension of government, providing a way for local property owners to prioritize and pay for improvements in their communities.

Research has shown that the greater the valuation of the properties in a BID, the more resources a BID has and the more effective it can be.

Research has shown that the greater the valuation of the properties in a BID, the more resources a BID has and the more effective it can be.

But critics nationwide take a broad view that BIDs, by their nature, exacerbate inequality by creating communities that have more access to better services than others in the same city.

“One big issue that we’ve also discussed, is their ability to disincentivize public investment in services,” said Jess Wunsch with New York University’s Furman Center. “So it's almost a way of cities, you know, deferring responsibility . . . and not delivering on services that they might otherwise.”

The center has done some of the most in-depth work on BIDs, finding clear benefits but also pitfalls, and remains neutral on their implementation.

TRANSPARENCY AND ACCOUNTABILITY

While BIDs can vote to raise taxes on their property owners for initiatives like landscaping and decorative lighting and uniformed safety forces, they do so in an advisory capacity.

State law leaves implementing the tax assessments or bond issuances necessary to finance the projects desired by the BID up to the municipality’s legislative body — in Rochester’s case, that means the City Council.

Still, the notion that BIDs operate outside the auspices of government is true in practice.

RELATED: Read the New York state law governing BIDs

Their operations tend to fly under the radar in most cities. They are hyperlocal and their meetings are poorly publicized. Most media outlets lack the resources or interest to cover them in any depth.

The High Falls Business Improvement District is a prime example of a BID that has gotten little scrutiny. Its most visible contribution to the neighborhood was financing the repainting of faded advertisements for businesses of yesteryear on building facades.

The dearth of scrutiny of BIDs elsewhere has occasionally resulted in waste and abuse.

For instance, New York City auditors found that a BID overseeing the so-called “Diamond District” in Manhattan engaged in “gross financial mismanagement” by authorizing security services for a building outside the district and paying the district’s executive director an outsized salary.

Last year, controversy swirled around a vote to renew a BID in the Adams Morgan neighborhood of Washington, D.C., when dozens of businesses there cried that the board of directors was poorly managed and mostly for the benefit of a few.

Last year, controversy swirled around a vote to renew a BID in the Adams Morgan neighborhood of Washington, D.C., when dozens of businesses there cried that the board of directors was poorly managed and mostly for the benefit of a few.

But there are also examples of good stemming from BIDs in those same cities.

One district in Manhattan created a mobile application to connect residents with businesses. Another in Washington provides outreach to the homeless.

‘ARTWASHING’ OR HOGWASH?

It may seem odd to anyone unfamiliar with civic battles over BIDs that artists are the frontline of opposition. But artists occupy a unique role in the BID landscape.

Business improvement districts often enlist artists to help make the neighborhoods they manage more attractive to investors. Indeed, Rochester’s most prominent artist, Shawn Dunwoody, is on an advisory board advocating for a downtown BID.

Such teamwork has proven effective elsewhere.

Last year, the Meatpacking Business Improvement District in New York City touted its success working with a minority-owned arts organization to celebrate Black culture through street art and performances.

Last year, the Meatpacking Business Improvement District in New York City touted its success working with a minority-owned arts organization to celebrate Black culture through street art and performances.

That kind of collaboration was the idea behind the Rochester Downtown Development Corp.’s call for artists to paint storefront windows downtown.

But artists objected to the plea on several grounds. They felt snubbed by not being consulted before the call was publicized. They were offended at what they perceived as the portrayal of downtown as being void of arts programming. And they were insulted by the initial offer to pay artists $500 for their work.

The Rochester Downtown Development Corp. later scaled up the pay to between $3,000 and $3,500, but by that time, the damage had been done.

Artists accused the agency of “artwashing,” a term used to describe the use of artists and artwork to whitewash clandestine efforts to gentrify a neighborhood.

Some went further to propose that the Rochester Downtown Development Corp. turn over its budget for public art — about $175,000 — to at least 10 city arts organizations for them to create arts programming.

The agency flatly rejected the proposal, reasoning that the money was slated for physical improvements and public art downtown, not art programming. Eventually, the agency shelved its proposal to pay artists to paint windows.

The agency flatly rejected the proposal, reasoning that the money was slated for physical improvements and public art downtown, not art programming. Eventually, the agency shelved its proposal to pay artists to paint windows.

Esposito, with Empire State Development, said he was not surprised at the criticism and anticipated there would be more to come, from artists, and other segments of the community.

“And that’s not bad, right?” Esposito said. “There’s all kinds of different types of art and levels of it. But I think it’s important that the arts community, such that it is, has a voice and a big one.

“In all of these conversations, we’re trying to find how to how to achieve that in a constructive collaborative way. And it's not easy,” he said. “And it certainly has had some challenges in the recent past. But I’m confident we’ll get there.”

WHAT IS A BID?

A business improvement district is an area with defined boundaries created by property owners who have agreed to tax themselves for services and quality-of-life improvements they want and that their government may be unable or unwilling to provide.

LIKE WHAT IMPROVEMENTS?

Improvements can be things like special events, lighting, sanitation, marketing, beautification, public art, hospitality, and security services.

ARE THESE THINGS COMMON?

Yes. There are more than 1,200 around the country. New York City alone has more than 70 of them. Syracuse has one. So does Schenectady. They’re everywhere. In fact, Rochester has one operating in the High Falls District.

WHO’S BEHIND THE DOWNTOWN ‘BID’?

This gets a little complicated. So, try to follow along.

The short answer is that mostly economic development interests and political forces are behind the push for a downtown BID.

The long answer is that something called the Rochester Downtown Partnership is behind it.

WHAT IS THE ROCHESTER DOWNTOWN PARTNERSHIP?

Rochester Downtown Partnership is a new nonprofit organization created by those aforementioned economic development interests and political forces.

It was created by the Rochester Downtown Development Corp., the city, and Finger Lakes Empire State Development, an arm of the state, for the sole purpose of planning for and eventually managing a downtown BID.

There are 17 members on the board, the vast majority of whom are movers and shakers in local business and political circles. One member is the artist Shawn Dunwoody.

Its day-to-day operations are currently handled by the Rochester Downtown Development Corp.

WHO’S FUNDING THIS EFFORT?

Mostly taxpayers. About $5 million has been set aside for the effort.

The bulk of it — about $3 million — is in the form of a grant from the $50 million “ROC the Riverway” initiative, a series of public works projects along the Genesee River downtown.

The rest of the bankroll consists of $1 million in private donations, mostly from downtown business and property owners, and revenue from the Rochester Downtown Development Corp., which is primarily funded by corporations, institutions, and real estate companies.

They had been invited there by the city’s foremost cheerleader of downtown, Heidi Zimmer-Meyer, the longtime president of the Rochester Downtown Development Corp., a nonprofit whose mission is to attract investment in the corridor.

She wanted to talk about a vision she and city officials shared for creating something called a “business improvement district” downtown, and ask for their ideas and support for a plan to help kick it off. That plan included a call for artists to paint storefront windows to “enhance the vibrancy” of the neighborhood.

The news did not go over well with the room.

Artists wondered whether she was aware of their existing efforts to create a lively downtown. They scoffed at the idea of an economic development agency coordinating art calls. They questioned why, if there was money to spend on art, it wasn’t being turned over to arts organizations, whose lack of public funding is well documented.

Within weeks, many of the artists there would dismiss the plan as literal window dressing intended to push through a concept that they argued could potentially drive artists out of the neighborhood they were being asked to “enhance.”

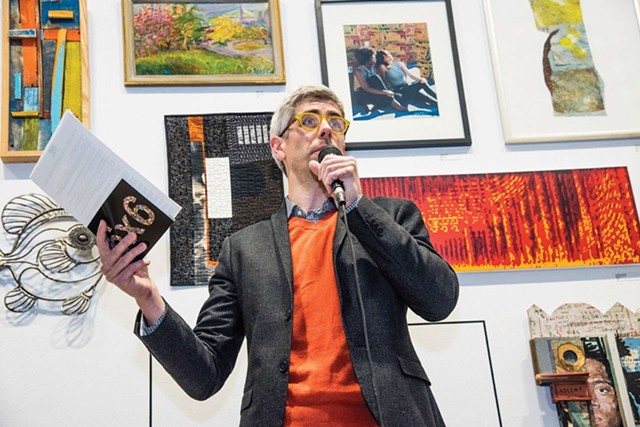

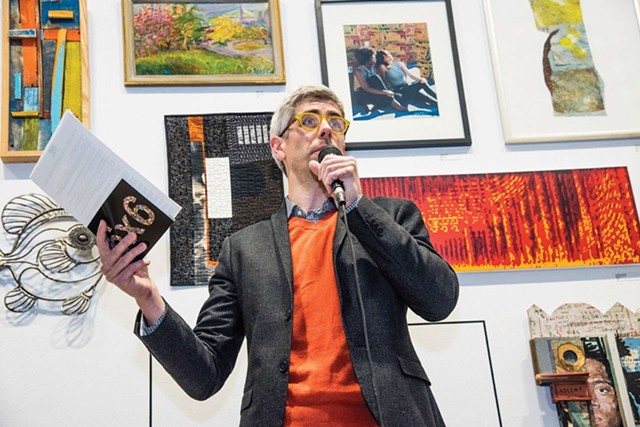

- PHOTO BY MAX SCHULTE

- The downtown Rochester skyline.

Artists have launched an offensive in the form of protests, social media campaigns, and a website called nobidroc.com — as in “no business improvement district” in Rochester. More than 650 people and counting have signed a related online petition.

When supporters began marketing their efforts with the tagline “Downtown Definitely,” the artists turned the motto on its head with their own version: “Downtown Dubiously.”

“They seem to want arts and culture to factor heavily into their plans, yet there was no transparent process or meaningful art community input,” said Bleu Cease, the executive director of the Rochester Contemporary Art Center on East Avenue and a leader in the movement to stop a business improvement district.

- PHOTO PROVIDED

- Bleu Cease, executive director of the Rochester Contemporary Art Center.

The vote was to formally begin a planning process to get the district up and running by 2024. Officials said they wanted time to clarify and answer myriad concerns that critics have raised. They might try again for a vote in August.

“People are thinking already, ‘Oh, this is a done deal,’” Evans said. “This is the beginning phases. This is not a fait accompli.”

Supporters of the proposed business improvement district say opponents are fearmongering and have it wrong.

The goal, they insist, is double-barreled: activate street vitality and enhance promotional efforts to bring people downtown and to other spaces that the city, the state, and private investors have sunk hundreds of millions of dollars into rehabbing.

“We’ve been hearing complaints for years about how dead downtown streets are,” said Zimmer-Meyer, who retired in June.

- PHOTO BY JACOB WALSH

- Heidi Zimmer-Meyer, the former head of Rochester Downtown Development Corp., was a champion for the creation of a downtown business improvement district. She retired in June and was replaced by Galin Brooks.

Business improvements districts, known as BIDs, are public-private partnerships.

Property owners in a defined area agree to pay additional taxes for services and quality-of-life improvements that the local government may be unable or unwilling to provide.

These can be things like special events, lighting, sanitation, marketing, beautification, public art, hospitality, and security services.

These districts began popping up in the United States in the mid-1970s, and cities across the country began embracing them ever since they were credited with helping transform Times Square and Union Square in New York City from dens of seediness to thriving tourist destinations. Today there are more than 1,200 BIDs nationwide.

Rochester created one in High Falls in 2005 without controversy. But a muddled attempt at organizing a downtown BID collapsed a decade ago.

- PHOTO BY MAX SCHULTE

- A view of the High Falls district from the south.

The catalyst for the latest push was the realization of a series of state- and city-funded public works projects along the Genesee River downtown and East Main Street.

Some $5 million has been set aside to create an entity to manage and promote those efforts, most of that in taxpayer money in the form of a state grant. The rest consists of $1 million in private donations, mostly from downtown business and property owners, and revenue from the Rochester Downtown Development Corp., which is primarily funded by corporations, institutions, and real estate companies.

“We need better organization, coordination on all of these redevelopment efforts and promotional efforts,” said Vinnie Esposito, who oversees New York state’s regional economic development efforts, specifically in the Finger Lakes, and supports the concept of a downtown BID.

“It’s not good enough just to improve a park and a trail and a public space,” he said. “What we really need to do is then promote and activate, and make those spaces come alive.”

- PHOTO BY MAX SCHULTE

- Parcel 5 was the site of the "Midday Bash," part of the Rochester Downtown Development Corp.'s "Downtown Definitely" campaign to draw people to the city's center with food trucks, music, lawn games, and fitness instructors.

Their opposition hews closely to that of critics of BIDs elsewhere who say the districts serve the interests of real estate developers by providing them the means to impose an unnecessary tax that could be passed along to tenants in the form of higher rents. They call them “classist” and “undemocratic,” and argue they lead to gentrification.

Opponents in Rochester have gone so far as to classify the proposed district as “21st century redlining.”

- PHOTO BY MAX SCHULTE

- Parcel 5 was the site of the "Midday Bash," part of the Rochester Downtown Development Corp.'s "Downtown Definitely" campaign to draw people to the city's center with food trucks, music, lawn games, and fitness instructors.

“Do we want to turn downtown Rochester into a privatized oasis of phony vitality?” asked Kelly Cheatle, a vocal opponent who is the artistic director at Airigami, a company on State Street near Lyell Avenue that creates intricate balloon arrangements for local and national clients.

“Do we want to give wealthy developers the power to hire private security to secure their vision of a ‘vital’ downtown?” Cheatle asked. “Do we want a secretive board to be able to levy taxes without public scrutiny? No.”

- PHOTO BY MAX SCHULTE

- Kelly Cheatle protests Rochester Downtown Development Corp.'s push for a business improvement district downtown outside of a RDDC meeting at the Holiday Inn Rochester in May.

SHADOW GOVERNMENT OR ECONOMIC ENGINE?

Business improvement districts vary in size and scope, and must be authorized through a multistep process that officials here say will take two years or more and requires buy-in from a majority of property owners in the designated area.

That process includes, among other things, devising a map of the district, proposing an annual budget, outlining how much property owners will pay, and public hearings on the matter. None of those things has happened yet.

That has not stopped opponents, though, from pushing the narrative that BIDs are secret societies, accountable to no one.

“If it’s not stopped,” reads the introduction at nobidroc.com, “a BID would work behind closed doors to make rules, control access to public spaces, and spend public money without transparency and no public accountability.”

- A screenshot of the website nobidroc.com.

The Evans administration backed that interpretation in correspondence with the City Council recently. The administration also noted that the city can impose a lifespan on the existence of a BID and force one to shut down.

State law also requires BIDs in cities like Rochester to include three members on their boards who are appointed respectively by the mayor, the chief financial officer, and the City Council. Opponents here have dismissed those posts as “token” representation.

To some degree, these districts function as an extension of government, providing a way for local property owners to prioritize and pay for improvements in their communities.

- PHOTO BY MAX SCHULTE

- Broad Street in downtown Rochester on a summer morning.

But critics nationwide take a broad view that BIDs, by their nature, exacerbate inequality by creating communities that have more access to better services than others in the same city.

“One big issue that we’ve also discussed, is their ability to disincentivize public investment in services,” said Jess Wunsch with New York University’s Furman Center. “So it's almost a way of cities, you know, deferring responsibility . . . and not delivering on services that they might otherwise.”

The center has done some of the most in-depth work on BIDs, finding clear benefits but also pitfalls, and remains neutral on their implementation.

TRANSPARENCY AND ACCOUNTABILITY

While BIDs can vote to raise taxes on their property owners for initiatives like landscaping and decorative lighting and uniformed safety forces, they do so in an advisory capacity.

State law leaves implementing the tax assessments or bond issuances necessary to finance the projects desired by the BID up to the municipality’s legislative body — in Rochester’s case, that means the City Council.

Still, the notion that BIDs operate outside the auspices of government is true in practice.

RELATED: Read the New York state law governing BIDs

Their operations tend to fly under the radar in most cities. They are hyperlocal and their meetings are poorly publicized. Most media outlets lack the resources or interest to cover them in any depth.

The High Falls Business Improvement District is a prime example of a BID that has gotten little scrutiny. Its most visible contribution to the neighborhood was financing the repainting of faded advertisements for businesses of yesteryear on building facades.

The dearth of scrutiny of BIDs elsewhere has occasionally resulted in waste and abuse.

For instance, New York City auditors found that a BID overseeing the so-called “Diamond District” in Manhattan engaged in “gross financial mismanagement” by authorizing security services for a building outside the district and paying the district’s executive director an outsized salary.

- PHOTO BY MAX SCHULTE

- Franklin Street in downtown Rochester.

But there are also examples of good stemming from BIDs in those same cities.

One district in Manhattan created a mobile application to connect residents with businesses. Another in Washington provides outreach to the homeless.

‘ARTWASHING’ OR HOGWASH?

It may seem odd to anyone unfamiliar with civic battles over BIDs that artists are the frontline of opposition. But artists occupy a unique role in the BID landscape.

Business improvement districts often enlist artists to help make the neighborhoods they manage more attractive to investors. Indeed, Rochester’s most prominent artist, Shawn Dunwoody, is on an advisory board advocating for a downtown BID.

Such teamwork has proven effective elsewhere.

- PHOTO BY MAX SCHULTE

- Shawn Dunwoody works on a mural on Scio Street while chatting with Bleu Cease, executive director of the Rochester Contemporary Art Center. Dunwoody is the lone artist advising the effort to create a downtown BID. Cease is a leading critic of the plan.

That kind of collaboration was the idea behind the Rochester Downtown Development Corp.’s call for artists to paint storefront windows downtown.

But artists objected to the plea on several grounds. They felt snubbed by not being consulted before the call was publicized. They were offended at what they perceived as the portrayal of downtown as being void of arts programming. And they were insulted by the initial offer to pay artists $500 for their work.

The Rochester Downtown Development Corp. later scaled up the pay to between $3,000 and $3,500, but by that time, the damage had been done.

Artists accused the agency of “artwashing,” a term used to describe the use of artists and artwork to whitewash clandestine efforts to gentrify a neighborhood.

Some went further to propose that the Rochester Downtown Development Corp. turn over its budget for public art — about $175,000 — to at least 10 city arts organizations for them to create arts programming.

- PHOTO BY MAX SCHULTE

- Nicole Bruno protests Rochester Downtown Development Corp.’s push for a business improvement districtoutside a meeting of the agency at the Holiday Inn.

Esposito, with Empire State Development, said he was not surprised at the criticism and anticipated there would be more to come, from artists, and other segments of the community.

“And that’s not bad, right?” Esposito said. “There’s all kinds of different types of art and levels of it. But I think it’s important that the arts community, such that it is, has a voice and a big one.

“In all of these conversations, we’re trying to find how to how to achieve that in a constructive collaborative way. And it's not easy,” he said. “And it certainly has had some challenges in the recent past. But I’m confident we’ll get there.”

- PHOTO BY MAX SCHULTE

- Parcel 5 was the site of the "Midday Bash," part of the Rochester Downtown Development Corp.'s "Downtown Definitely" campaign to draw people to the city's center with food trucks, music, lawn games, and fitness instructors.

'BID's BY THE BASICS

A business improvement district is an area with defined boundaries created by property owners who have agreed to tax themselves for services and quality-of-life improvements they want and that their government may be unable or unwilling to provide.

LIKE WHAT IMPROVEMENTS?

Improvements can be things like special events, lighting, sanitation, marketing, beautification, public art, hospitality, and security services.

ARE THESE THINGS COMMON?

Yes. There are more than 1,200 around the country. New York City alone has more than 70 of them. Syracuse has one. So does Schenectady. They’re everywhere. In fact, Rochester has one operating in the High Falls District.

WHO’S BEHIND THE DOWNTOWN ‘BID’?

This gets a little complicated. So, try to follow along.

The short answer is that mostly economic development interests and political forces are behind the push for a downtown BID.

The long answer is that something called the Rochester Downtown Partnership is behind it.

WHAT IS THE ROCHESTER DOWNTOWN PARTNERSHIP?

Rochester Downtown Partnership is a new nonprofit organization created by those aforementioned economic development interests and political forces.

It was created by the Rochester Downtown Development Corp., the city, and Finger Lakes Empire State Development, an arm of the state, for the sole purpose of planning for and eventually managing a downtown BID.

There are 17 members on the board, the vast majority of whom are movers and shakers in local business and political circles. One member is the artist Shawn Dunwoody.

Its day-to-day operations are currently handled by the Rochester Downtown Development Corp.

WHO’S FUNDING THIS EFFORT?

Mostly taxpayers. About $5 million has been set aside for the effort.

The bulk of it — about $3 million — is in the form of a grant from the $50 million “ROC the Riverway” initiative, a series of public works projects along the Genesee River downtown.

The rest of the bankroll consists of $1 million in private donations, mostly from downtown business and property owners, and revenue from the Rochester Downtown Development Corp., which is primarily funded by corporations, institutions, and real estate companies.

- PHOTO BY MAX SCHULTE

- The downtown Rochester skyline.

WHAT'S NEXT?

If the City Council votes to proceed . . .

The year ahead will be spent creating the district plan, including mapping the boundaries, devising an annual budget, and detailing how much property owners would pay.

MID-TO LATE SUMMER 2023

Petitioning, during which time organizers need to gather support from the owners of at least 51% of the assessed valuation of all property within the boundaries.

FALL/WINTER 2023

A series of procedural steps sends the matter back to City Council for a public hearing and vote. Then, to the state comptroller for sign off. Then back to City Council for final approval.

SPRING 2024

City Council votes on the boundaries and the management plan.

JULY 2024

The BID has to be in place by July in order for the add-on fee or “tax” that will fund it to be included in tax bills. Miss that and the timetable shifts to 2025.

David Andreatta is CITY's editor. He can be reached at [email protected].

Brian Sharp is a reporter for WXXI News, a media partner of CITY. He can be reached at [email protected].

The year ahead will be spent creating the district plan, including mapping the boundaries, devising an annual budget, and detailing how much property owners would pay.

MID-TO LATE SUMMER 2023

Petitioning, during which time organizers need to gather support from the owners of at least 51% of the assessed valuation of all property within the boundaries.

FALL/WINTER 2023

A series of procedural steps sends the matter back to City Council for a public hearing and vote. Then, to the state comptroller for sign off. Then back to City Council for final approval.

SPRING 2024

City Council votes on the boundaries and the management plan.

JULY 2024

The BID has to be in place by July in order for the add-on fee or “tax” that will fund it to be included in tax bills. Miss that and the timetable shifts to 2025.

David Andreatta is CITY's editor. He can be reached at [email protected].

Brian Sharp is a reporter for WXXI News, a media partner of CITY. He can be reached at [email protected].