It's reasonable to wonder whether Terry Dade knows what he's gotten himself into as the new superintendent of Rochester's schools. But Dade, who is days into a job that is certain to test him, is hardly naive. He's keenly aware of the public's skepticism, frustration, and disillusionment about the district. And in a recent interview with CITY, he was candid, confident, and focused.

Dade is personally familiar with the hurdles many urban children and their families have to overcome. He never knew his mother. He was raised by his father, who had full custody, by his grandmother, and, when he was in elementary school, his step-mother. The family lived in Section 8 housing in Reston, Virginia, a planned community about 20 miles west of Washington, DC.

Reston's residents have included both low-income families and more affluent ones. "So I continued to live in Section 8 housing while also attending a great school system," he said. Education "absolutely helped me get to where I am today, so I just know the benefit that it can have on a life."

Dade has degrees from the University of Virginia and taught in elementary schools for several years. And then he was accepted in New Leaders for New Schools, a program for educators who want to become principals in schools serving high-needs students.

- PHOTO BY RYAN WILLIAMSON

"I honestly feel that it's a calling to work within an urban district," he said. "There's nothing else that I wanted when I accepted my time with New Leaders for New Schools."

His first administrative position was as an assistant principal at a Washington, DC, elementary school, and he loved it. "That was where I felt like the work was happening," he said. "Folks all around were looking at: Could this be a model for urban education success? So I loved that."

At the time, Michelle Rhee, the hard-driving education reformer, was chancellor of the DC school system. Rhee, who took control of DC's troubled schools after the school board was stripped of its authority, wanted teacher pay and job security tied to student achievement rather than being based on teacher seniority. That made her a polarizing figure, but Dade has great respect for Rhee.

The year before joining the DC school system, he had taught in a charter school, which he calls "the most disheartening experience of my entire career." The reason: staff complacency.

Rhee, he said, didn't tolerate complacency: "I don't care what seat you were sitting in, you knew you had to have high expectations for yourself and for the students that you were serving."

Her philosophy, Dade said, was "This is not about adults in this district. It never will be about adults. It's going to be about our students. And she went about to kind of change that culture in the district."

'Leadership matters'

Dade's most recent job, in the public school system of Fairfax County, Virginia, a DC suburb, gave him experience with some of the challenges he'll face here. In Fairfax County, he was one of three regional superintendents, in charge of 45 schools serving about 37,000 students. In comparison, the Rochester school district has about 60 schools and 28,000 students.

His region, he said, was the Fairfax system's most diverse, and it is far more diverse than Rochester: 40 percent Hispanic, 30 percent white, 20 percent black, 10 percent Asian – most of them from families living in poverty, and a third of them English language learners.

Thirteen of the schools under his supervision weren't meeting state accreditation standards, a situation similar to that in New York, which imposes requirements on schools that are in "receivership" for persistently poor performance. And Dade had to develop a school improvement model much like the reforms required here.

Each of the 13 schools was very different, he says. One had serious "climate and culture" problems. "You can't get to academics," he said, "if you aren't even addressing how kids are feeling about school, whether parents are feeling engaged."

- PHOTO BY RYAN WILLIAMSON

In other schools, the problem was poor teaching, "so we really had to elevate their professional development of teachers." In some, the problem was leadership. "Leadership matters," Dade said, "and unfortunately some of the leaders at that time weren't in the best seat."

His approach, he said, was to talk to teachers and administrators, asking them to identify the barriers that were preventing them and their students from achieving their potential. Together, he said, they looked for ways to address their concerns. But he has no delusions.

"There are no five tried-and-true, 'if every school does these five things,' they're going to be successful," Dade said. If there were, he said, "I would have written a book by now and be traveling the country. It's not that easy."

Dade seems clear-eyed about the job he began on July 1, but he starts his tenure in Rochester in an unpredictable period. State Education Commissioner MaryEllen Elia has been extremely critical of the district's lagging performance, sentiments echoed by local Regents Wade Norwood and T. Andrew Brown. State Regents Wade Norwood and T. Andrew Brown have echoed Elia's concerns. And Mayor Warren wants the state to dissolve the school board and take over its operations for up to five years.

So far, state legislators have not taken up the issue, and the school board remains in control of the district. And so Dade will have to work with a board that has been criticized frequently for trying to usurp some of the superintendent's responsibilities. Dade's aware of that.

"The board and I are going into a two-day retreat in August," he said, "and my sincere hope is that we tackle the delineation of roles and responsibilities – knowing that it's not going to be perfect, but do we have it in writing, that we can always lean back on this to say, 'Here's why Terry's upset with this, because we said, clear as day, this is how we would operate.' Or: 'This is why the board is upset with Terry. It's clear as day, written.'"

And, he said, they'll discuss how adults should behave. "We have to be models for what our students, how they conduct themselves. So at the end of the day, I carry myself with the utmost professionalism. You'll never see me lose my cool, because our kids are watching."

Dade could benefit, in a roundabout way, from the ongoing, community-wide conversation about the district's future. He may be able to help the community better understand some of the district's most enduring problems and figure out how to fix them.

And not everything about the district is negative. Dade also inherits a graduation rate that's inching upward, though slowly. And most of the first schools that the state education department identified as failing have shown improvement.

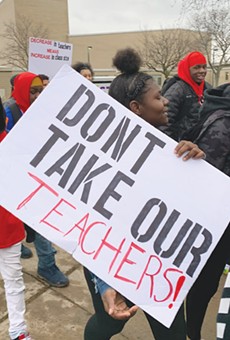

- PHOTO BY RYAN WILLIAMSON

Improving schools need support

Dade understands the unique challenges that urban districts face. It's not hard to find individual pockets of success in districts like Rochester, but it's hard to find entire high-poverty urban districts that are successful.

Among the challenges: "When you provide some schools with resources and support and then they start making success, everyone knows what happens to that support and resources. We start to take them away."

Just because a school improves, he said, that doesn't mean that teachers won't continue to need professional development every year, or that students won't need extended learning time.

"If you look all across the country," he said, "there's models of reform efforts where we throw X at schools, X at schools, X at schools, and then a new superintendent comes or a new governor comes or state ed changes, and then we're trying a whole new strategy. Imagine the teachers who live through numerous superintendents, principals who live through numerous: 'Now I have to learn this new approach, find the resources and support to shore up my teachers, and then the standards change, the strategies change."

Another challenge for urban districts: student mobility. "Students moving from school to school, in and out of district, in and out of charters: that is not a recipe for success," Dade said. Students who have been at the same school for five years, he said, are typically that school's more successful students.

"Every other year you might have a new crop of students and families coming in," Dade said. And while that's not an excuse for poor performance, he said, "it is something that we just can't negate as we look at what is going to be successful.

- PHOTO BY RYAN WILLIAMSON

Fundamental skills aren't enough

Despite the increase in Rochester's graduation rate, college administrators say that a sizeable number of graduates aren't prepared for college and have to take remedial classes.

"This is not just New York or Rochester-specific," Dade said. When a district is "just trying to make it over the hump and over the threshold," it's likely to focus on core skills – "and rightfully so," Dade said. "I don't fault anyone for that."

As urban districts improve their success at the foundational skills, he said, "then we can truly start looking at our students not only being able to walk across the stage but be successful in a two- or four-year college without paying for intervention, remedial courses, and the like."

"You and I aren't – our performance isn't based on a multiple choice test. We get to try things out, fail a few times, modify and revise as needed. And we depend on others around us to be successful at what we do. But our students are asked to just sit in a desk by themselves, answer a multiple-choice test, and have that be their determination of whether they're successful or not."

"I think until we enter that balance, we are going to continue to have students who might do well and get across the finish line for graduation or proficiency but still not be quite equipped to be successful in a two- or four-year college, in the military, and beyond, where they have to depend on others around them to be successful.

Absenteeism is an RCSD problem

Contributing to the Rochester district's challenges is its high rate of student absenteeism, and that's clearly an issue for Dade. Asked about it, he immediately brought up the issue of neighborhood schools.

"The chronic absenteeism rate here is nothing like I've seen anywhere," he said. "I want someone to be able to tell me: What are the percentage of students that actually go to their neighborhood school?"

For years, Rochester has had a school-choice program, in part based on requirements of the No Child Left Behind act, and on some school board members' belief that families shouldn't be forced to send children to schools they're not satisfied with. While many parents and residents are calling for a return to neighborhood schools, many parents pick schools that are not nearby because they fear for their children's safety and they want them to ride a bus to school.

When his students came to school from all around the district, "those were the students I had the most problems with engaging parents in getting them to school on time," Dade said.

In Rochester, he suggested, School 23 in the Park Avenue area likely has a higher percentage of students coming from the surrounding neighborhood. "Some of our other schools might have a percentage that wouldn't allow me to sleep very well tonight," he said. "I think that drives absenteeism rates. Just think of how many excuses you might have not to go to school if you live outside of the school boundary."

Dade said he wants to examine the district's busing policy and perhaps seek waivers from the state. And with interest increasing in community schools in Rochester, Dade said, "What if busing policies change for community schools, just as a start?" What, he said, if that enabled Rochester to have community schools with attendance rates of 90 percent?

"I think they would tell an amazing story of parents truly engaged," he said, "attendance rates through the roof, true pride in giving back to the community through service projects and things of that nature."

Parent engagement, in fact, is a problem for the Rochester district, and Dade thinks community schools, drawing from their surrounding neighborhood, could help. It matters, he suggested, whether after a long day at work, parents can walk a few minutes to their child's school or "have to travel by whatever means back out to a school outside of your neighborhood."

Some parents say they don't feel welcome in their child's school. "I do think we need to look closely at making sure our parents are absolutely welcome, that we're looking at different strategies for engaging," he said. "But then I would love to unpack what parent engagement means for this community."

When he was a principal, he said, parent engagement meant being able to call parents when their child was missing school or having other problems and getting their support. "For me," he said, "parent engagement doesn't mean a physical presence, necessarily, in the school building, because our parents are dealing with so many things just to do right by their kids."

- PHOTO BY RYAN WILLIAMSON

Special ed is a top priority

Also on Dade's agenda as he starts his work here: a recent agreement with the Empire Justice Center to improve the district's poorly managed special education services – "marching orders agreed to by all parties," as Dade put it.

Engaging parents in the special education process, ensuring that "we're kind of dotting our I's and crossing our T's – non-negotiable," Dade said. "We can't not meet deadlines and things of that nature."

"From the time that a parent requests assessments," Dade said, "schools and teams have to be on point with those pieces. And then there's the heavier lift around quality of instruction, proficiency rates for students, disproportionality in our suspension rates and things of that nature."

The Rochester school district needs to show the same progress with its special education students as it does with its black students or white students "or any other subgroup," he said.

'Help us move our kids forward'

Among the ways Rochester has tried to improve struggling schools is to partner with the University of Rochester to operate East High School. Critics of that partnership complain that East's success is due in part to additional money and other resources. Dade, however, applauds partnerships with outside organizations.

"If you look at some of the more successful initiatives across the country for urban education," he said, "they involve higher education. I mean, who better to help frame what a successful graduate might look like and need?"

And, he added: "It doesn't have to be with the university. I would love to see more partnerships with hospitals and other businesses. I don't care who it is, but take a vested interest in your community and the kids that you serve, and you're going to achieve great things. So I don't want to say I'm 100 percent on 'We need to replicate that partnership,' but if I could see more true, hospital, business partnerships, things of that nature that truly have that back-and-forth synergy, we're going to be that much more successful."

Those kinds of partnerships, Dade said, are not only bringing additional resources: "They're bringing their own stakeholder groups to say, This is why we believe in this school or this community. Help us move our kids forward."

Know your students

Also among the Rochester district's many challenges: The majority of its teachers are white and the majority of its students are not. The district "absolutely" has to pay attention to diversifying its teaching staff, he said, because there will always be inherent biases. And he tells a personal story of a different kind of inherent bias.

While he had intended to work in urban education, his first teaching job was in a rural part of Virginia. As he would have in an urban school, he kept asking his students what they were doing to prepare for college. A parent set him straight, however: "Mr. Dade, she is not going to college. She's going to help run our farm. That's what we do. This is how we survive as a family."

"It hit me in the gut," he said, "because I was bringing what my background told me was important for education."

"I had no right to instill my belief system there," he said.

Understanding what it's like to be in the shoes of someone of another race "is always going to be something that we're going to have to work on," he said.

"I don't think we can professionally develop that," Dade said.

What school districts can do, he said, is to have conversations with teachers every year: "Are you actually going into the community to understand where your students are living and coming from? Do you do home visits to have a better understanding?"

" Our lessons: Are they culturally responsive? Meaning, if you're whole class is into hip-hop, you better put some hip-hop into your lessons or you're dead in the water."

- PHOTO BY RYAN WILLIAMSON

'The negative stories to positive broke my heart'

While Dade recognizes the problems the district has experienced, he said he also wants the community to focus on the district's strengths. "When I was researching the district," he said, "the negative stories to positive broke my heart. So I hope I'm a contributing factor to helping change the narrative and starting to celebrate more what we're doing well in all the challenges we have."

On the day of CITY's interview, Dade hadn't yet met Mayor Lovely Warren or the local Regents, all of whom have been sharply critical of the district. Asked what he hopes to impress on them when he does meet them, he gave this answer:

"It's easy to say 'We're going to do this, that, or the other' on July 1. But when I say we will operate as a family – not just on July 1, but on November 15, in the cold, dreary months of February in our city, we will operate as a family – I need you to look at my leadership at all of those points along the way to see if I'm holding true to that."