Auditors from the state Comptroller’s Office have begun scrutinizing the Rochester City School District’s 2018-19 budget to figure out how the district spent an estimated $30 million it didn’t have – an endeavor the state predicts could take six months to a year to conclude.

Meanwhile, on Tuesday Superintendent Terry Dade is expected to update the school board on what the district’s own investigation has found so far.

It may be some time before the public learns just what happened, and why apparently so few people inside the system knew about the overspending until last month. But research by a local education analyst provides some insight into how the shortfall happened.

The fundamental cause of the shortfall is easy to spell out: “too much spending in too many places” and fewer opportunities to save money, said the researcher, Eamonn Scanlon, education analyst with The Children’s Agenda. At the core, Scanlon said, is a long-standing district problem: its structural deficit. Costs are increasing at a faster rate than revenue.

Urban school districts like Rochester’s serve thousands of poor children, and many education advocates insist those districts need more money than they get. Nevertheless, when school districts spend beyond their means, they jeopardize not only themselves but also their city governments, which are charged with raising local revenue for education. The Rochester district’s latest problems have broadened appeals for state involvement in the district’s operations.

In a recent blog on the Children’s Agenda website, Scanlon focused on the conditions in which the $30 million shortfall was born. He paid particular attention to the period from January through March 2018, when district staff were nearing the end of their budget preparation for the coming year.

What did the district spend that $30 million on? The district’s financial records, Scanlon wrote, indicate that it went for things the district has to provide: transportation, employee benefits, substitute teachers, and charter school tuition. The district didn’t budget enough for them, though. “Cost projections for those areas were too low, sometimes by more than $10 million,” Scanlon wrote.

Running over budget in some areas, Scanlon noted, isn’t uncommon. And when that happens, school districts look for ways to reduce expenses somewhere else to offset the increases. But the Rochester school district had few other budget categories where it could make reductions.

Adding to the difficulty of creating a balanced budget that year, Scanlon wrote, were some unexpected challenges and the distraction from a major new initiative by the superintendent.

In his blog, Scanlon cited these problems:

• Faulty budget projections, lack of transparency, and “unsustainable financial gimmicks.”

The 2018-19 budget, Scanlon wrote, “included many risky and in some cases dishonest cost projections, because of a flawed budget-making process,” too little input from staff outside of the finance department, and “a host of external pressures.”

• Superintendent Barbara Deane-Williams’ “Path Forward” initiative.

Soon after Barbara Deane-Williams became superintendent in August 2016, she embarked on a several-month “listening tour,” talking to students, parents, teachers, and administrators. In 2017, based on what she had learned, she and her staff started working on a 10-year education and facilities plan that they named “Path Forward.”

It was an ambitious plan, and the work took months. Toward the end of that period, the district had to start work on the budget for the next academic year.

The Path Forward initiative, Scanlon wrote, “consumed much of (Deane-Williams’s) leadership team’s time during the months leading up to the release of the 2018-2019 draft budget. Her team’s preoccupation with Path Forward left the financial decisions to the finance department with seemingly little input from other department leaders. This delayed the budget making process, and resulted in the finance department presenting an unbalanced budget on March 27.”

• The death of teenager Trevyan Rowe in March of 2018, which added to the demands and pressure at a crucial time in the district.

This tragedy underscored the dysfunction and multiple changes in leadership within the special education department,” Scanlon wrote. “The special education department was under threat of legal action for being out of compliance with state and federal disability laws, and was negotiating with Empire Justice to develop a consent decree in place of a lawsuit.”

• Intense pressure to increase staffing in some areas.

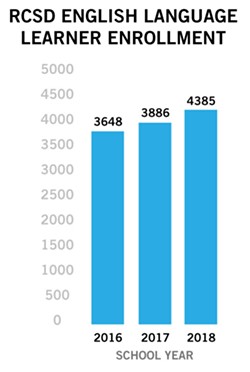

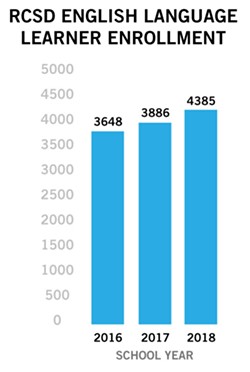

In the months following Hurricane Maria in September 2017, many families moved to Rochester from Puerto Rico. As a result, the Rochester school district had 560 new students needing English Language Learner classes, and the district already had a shortage of bilingual and English as a second language staff.

Deane-Williams was also pushing for additional reading teachers to counter the abysmally low test scores of the district’s elementary school students.

As Deane-Williams pushed for more staffing and the district tried to cope with the challenges of Path Forward and special education, the staff creating the 2018-19 budget had to adjust their budget projections, increasing the expense projections in some areas and looking for ways to save money in other areas. In the process, it did what school districts, businesses, and families do: it moved money around in the budget.

Moving money around isn’t uncommon for school districts. While some of their expenses are fairly predictable, some aren’t.

Rochester and the state’s other large-city school districts also have a challenge that other New York districts don’t: they don’t raise their own revenue. Local, state, and federal governments provide some of it. But for the big urban districts, with large numbers of high-needs students, “a significant part of their revenue comes from grants,” Scanlon says.

Expanding on his concerns about the 2018-19 budget in an interview last week, Scanlon described the role grants play in school budgets. A school district might start a year paying for a reading program out of the district’s general fund, knowing that it will get a grant later in the year. When the grant arrives, the general fund money can be used for another expense, so that expense gets moved from one place to another in the budget.

“Grant funding is just very unstable revenue,” Scanlon said. “Money is constantly coming in and out.”

“That’s sort of the big picture here,” Scanlon said. “Money gets moved around for various reasons.” And in the Rochester district, “money moves around a lot . . . and it’s never really explained why.”

That makes it hard to track the changes throughout the year, even for school board members.

Normally, as the finance department creates a budget and requests are made for additions and subtractions, “there is a back and forth process” discussing changes with staff outside the finance office, Scanlon said. But as the district worked on the 2018-19 budget, “people were just really distracted,” Scanlon said, because of everything else going on in the district.

As pressure mounted to increase staff in some areas and the deadline for completing the budget got closer, district staff made adjustments to the budget. “There was about an $8 million or $9 million write-down in the costs for retirement and benefits between the draft budget and the adopted budget,” Scanlon said. The projected cost of employee benefits “went from $36 million to $34 million, health and dental from 86 to 85.”

Scanlon thinks the district also low-balled the cost of charter school tuition, state per-pupil aid that the district has to pass on to charter schools serving Rochester students. Although the district anticipated that 450 more students would be attending charter schools the next year, it didn’t budget nearly enough for their tuition, Scanlon said.

Worse, in crafting the budget, the district “took the guardrails off,” Scanlon said.

What Scanlon calls ”guardrails” are expense areas where money that is budgeted is usually underspent or not spent. In other words, they are budget safety valves. One guardrail is the district’s contingency fund, “which is money specifically for overruns,” Scanlon said. For the 2018-19 budget, district staff reduced the contingency fund to $350,000, from the original $3.25 million.

The other guardrail is the amount the district thinks it will save each year when budgeted staff positions aren’t filled. In the initial budget, the district projected just over $8 million for vacancy savings. The final budget raises that to a $24.48 million – an increase in projected “revenue” of about $16 million.

Together, that meant the district had reduced its flexibility in spending by nearly $20 million, Scanlon said.

Budget-making for Rochester and New York’s other urban school districts is tough, Scanlon said.

“It’s more difficult, because they have no borrowing authority, so they are dependent on the state for any increase,” he said. The districts “are completely hostage to whatever the state decides will be their increase or decrease in a given year.”

And, Scanlon said, “when you have a very high-needs population, with a much higher proportion of English language learners and special education programming, that is more expensive and harder to staff.”

“A special needs student is 250 percent more expensive to educate than a general education student,” Scanlon said. “It’s a huge piece of the budget and a complex one, and so we can’t just look at per-pupil spending across districts. It’s really about the individual needs of each child that need to be taken into account.”

Do the urban districts get enough state funding? “That’s a complicated question,” Scanlon said. The state has a formula for determining the aid that districts should get. The Board of Regents calculates that foundation aid every year and tells the state Legislature what it should be providing to each district, Scanlon said.

But the state never puts in enough money to match that calculation, Scanlon said.

Based on that formula, Scanlon noted in his blog, “Rochester was owed $97 million in additional funding from the state during the 2018-19 school year.”

With that money, presumably, the Rochester school district wouldn’t have had the budget problems it had last year. And there’d be no state auditors at work in the district’s offices on Broad Street right now.

But the district didn’t get that money, and there’s no reason to think state legislators will have a change of heart any time soon. Meantime, the district will have to operate on the money it does get, despite its challenges and financial uncertainties.

As district officials create and oversee budgets, Scanlon said, they need a more transparent process so that the school board, staff, parents, and the community understand what the district is doing, how officials are planning its finances, and what changes officials are making as well why they’re making them.

“As long as RCSD faces a large structural deficit every year, lacks transparency and collaboration in its budget-making process, is perpetually responding to crises and external pressures, and uses unsustainable financial gimmicks to prop up spending, there will always be the potential for problems,” Scanlon wrote in his Children’s Agenda blog.

Meanwhile, on Tuesday Superintendent Terry Dade is expected to update the school board on what the district’s own investigation has found so far.

It may be some time before the public learns just what happened, and why apparently so few people inside the system knew about the overspending until last month. But research by a local education analyst provides some insight into how the shortfall happened.

- Eamonn Scanlon, education analyst at The Children's Agenda: The district's spending paid for things it had to provide, but it didn't budget enough for them.

The fundamental cause of the shortfall is easy to spell out: “too much spending in too many places” and fewer opportunities to save money, said the researcher, Eamonn Scanlon, education analyst with The Children’s Agenda. At the core, Scanlon said, is a long-standing district problem: its structural deficit. Costs are increasing at a faster rate than revenue.

Urban school districts like Rochester’s serve thousands of poor children, and many education advocates insist those districts need more money than they get. Nevertheless, when school districts spend beyond their means, they jeopardize not only themselves but also their city governments, which are charged with raising local revenue for education. The Rochester district’s latest problems have broadened appeals for state involvement in the district’s operations.

In a recent blog on the Children’s Agenda website, Scanlon focused on the conditions in which the $30 million shortfall was born. He paid particular attention to the period from January through March 2018, when district staff were nearing the end of their budget preparation for the coming year.

What did the district spend that $30 million on? The district’s financial records, Scanlon wrote, indicate that it went for things the district has to provide: transportation, employee benefits, substitute teachers, and charter school tuition. The district didn’t budget enough for them, though. “Cost projections for those areas were too low, sometimes by more than $10 million,” Scanlon wrote.

Running over budget in some areas, Scanlon noted, isn’t uncommon. And when that happens, school districts look for ways to reduce expenses somewhere else to offset the increases. But the Rochester school district had few other budget categories where it could make reductions.

Adding to the difficulty of creating a balanced budget that year, Scanlon wrote, were some unexpected challenges and the distraction from a major new initiative by the superintendent.

In his blog, Scanlon cited these problems:

• Faulty budget projections, lack of transparency, and “unsustainable financial gimmicks.”

The 2018-19 budget, Scanlon wrote, “included many risky and in some cases dishonest cost projections, because of a flawed budget-making process,” too little input from staff outside of the finance department, and “a host of external pressures.”

• Superintendent Barbara Deane-Williams’ “Path Forward” initiative.

Soon after Barbara Deane-Williams became superintendent in August 2016, she embarked on a several-month “listening tour,” talking to students, parents, teachers, and administrators. In 2017, based on what she had learned, she and her staff started working on a 10-year education and facilities plan that they named “Path Forward.”

It was an ambitious plan, and the work took months. Toward the end of that period, the district had to start work on the budget for the next academic year.

The Path Forward initiative, Scanlon wrote, “consumed much of (Deane-Williams’s) leadership team’s time during the months leading up to the release of the 2018-2019 draft budget. Her team’s preoccupation with Path Forward left the financial decisions to the finance department with seemingly little input from other department leaders. This delayed the budget making process, and resulted in the finance department presenting an unbalanced budget on March 27.”

• The death of teenager Trevyan Rowe in March of 2018, which added to the demands and pressure at a crucial time in the district.

This tragedy underscored the dysfunction and multiple changes in leadership within the special education department,” Scanlon wrote. “The special education department was under threat of legal action for being out of compliance with state and federal disability laws, and was negotiating with Empire Justice to develop a consent decree in place of a lawsuit.”

• Intense pressure to increase staffing in some areas.

In the months following Hurricane Maria in September 2017, many families moved to Rochester from Puerto Rico. As a result, the Rochester school district had 560 new students needing English Language Learner classes, and the district already had a shortage of bilingual and English as a second language staff.

Deane-Williams was also pushing for additional reading teachers to counter the abysmally low test scores of the district’s elementary school students.

As Deane-Williams pushed for more staffing and the district tried to cope with the challenges of Path Forward and special education, the staff creating the 2018-19 budget had to adjust their budget projections, increasing the expense projections in some areas and looking for ways to save money in other areas. In the process, it did what school districts, businesses, and families do: it moved money around in the budget.

Moving money around isn’t uncommon for school districts. While some of their expenses are fairly predictable, some aren’t.

Rochester and the state’s other large-city school districts also have a challenge that other New York districts don’t: they don’t raise their own revenue. Local, state, and federal governments provide some of it. But for the big urban districts, with large numbers of high-needs students, “a significant part of their revenue comes from grants,” Scanlon says.

Expanding on his concerns about the 2018-19 budget in an interview last week, Scanlon described the role grants play in school budgets. A school district might start a year paying for a reading program out of the district’s general fund, knowing that it will get a grant later in the year. When the grant arrives, the general fund money can be used for another expense, so that expense gets moved from one place to another in the budget.

“Grant funding is just very unstable revenue,” Scanlon said. “Money is constantly coming in and out.”

“That’s sort of the big picture here,” Scanlon said. “Money gets moved around for various reasons.” And in the Rochester district, “money moves around a lot . . . and it’s never really explained why.”

That makes it hard to track the changes throughout the year, even for school board members.

Normally, as the finance department creates a budget and requests are made for additions and subtractions, “there is a back and forth process” discussing changes with staff outside the finance office, Scanlon said. But as the district worked on the 2018-19 budget, “people were just really distracted,” Scanlon said, because of everything else going on in the district.

As pressure mounted to increase staff in some areas and the deadline for completing the budget got closer, district staff made adjustments to the budget. “There was about an $8 million or $9 million write-down in the costs for retirement and benefits between the draft budget and the adopted budget,” Scanlon said. The projected cost of employee benefits “went from $36 million to $34 million, health and dental from 86 to 85.”

Scanlon thinks the district also low-balled the cost of charter school tuition, state per-pupil aid that the district has to pass on to charter schools serving Rochester students. Although the district anticipated that 450 more students would be attending charter schools the next year, it didn’t budget nearly enough for their tuition, Scanlon said.

Worse, in crafting the budget, the district “took the guardrails off,” Scanlon said.

What Scanlon calls ”guardrails” are expense areas where money that is budgeted is usually underspent or not spent. In other words, they are budget safety valves. One guardrail is the district’s contingency fund, “which is money specifically for overruns,” Scanlon said. For the 2018-19 budget, district staff reduced the contingency fund to $350,000, from the original $3.25 million.

The other guardrail is the amount the district thinks it will save each year when budgeted staff positions aren’t filled. In the initial budget, the district projected just over $8 million for vacancy savings. The final budget raises that to a $24.48 million – an increase in projected “revenue” of about $16 million.

- The district has been under-budgeting its expense for substitute teachers for several years. (An earlier version of this chart contained incorrect totals for the 2018-19 budget year.)

Together, that meant the district had reduced its flexibility in spending by nearly $20 million, Scanlon said.

Budget-making for Rochester and New York’s other urban school districts is tough, Scanlon said.

“It’s more difficult, because they have no borrowing authority, so they are dependent on the state for any increase,” he said. The districts “are completely hostage to whatever the state decides will be their increase or decrease in a given year.”

And, Scanlon said, “when you have a very high-needs population, with a much higher proportion of English language learners and special education programming, that is more expensive and harder to staff.”

“A special needs student is 250 percent more expensive to educate than a general education student,” Scanlon said. “It’s a huge piece of the budget and a complex one, and so we can’t just look at per-pupil spending across districts. It’s really about the individual needs of each child that need to be taken into account.”

Do the urban districts get enough state funding? “That’s a complicated question,” Scanlon said. The state has a formula for determining the aid that districts should get. The Board of Regents calculates that foundation aid every year and tells the state Legislature what it should be providing to each district, Scanlon said.

But the state never puts in enough money to match that calculation, Scanlon said.

Based on that formula, Scanlon noted in his blog, “Rochester was owed $97 million in additional funding from the state during the 2018-19 school year.”

With that money, presumably, the Rochester school district wouldn’t have had the budget problems it had last year. And there’d be no state auditors at work in the district’s offices on Broad Street right now.

But the district didn’t get that money, and there’s no reason to think state legislators will have a change of heart any time soon. Meantime, the district will have to operate on the money it does get, despite its challenges and financial uncertainties.

As district officials create and oversee budgets, Scanlon said, they need a more transparent process so that the school board, staff, parents, and the community understand what the district is doing, how officials are planning its finances, and what changes officials are making as well why they’re making them.

“As long as RCSD faces a large structural deficit every year, lacks transparency and collaboration in its budget-making process, is perpetually responding to crises and external pressures, and uses unsustainable financial gimmicks to prop up spending, there will always be the potential for problems,” Scanlon wrote in his Children’s Agenda blog.