- PHOTO BY MATT BURKHARTT

- "The bloodlines of Rochester's reggae scene runs through The Majestics, above. "But we're not Jamaicans, man," says the band's keyboardist Ron Stackman, left. "We're not going to sound like Jamaicans no matter what we do. It ain't happening."

There are The Majestics, Giant Panda Guerilla Dub Squad, Ignite Reggae Band, Noble Vibes, Mosaic Foundation, Personal Blend, The Medicinals, and The Forest Dwellers.

With the exception of Ignite, the majority of the bands are white and have no ties to Jamaica — the birthplace of reggae — beyond a deep love for the music.

But the story of reggae in the Rochester area has always been about its musicians coming to terms with white appropriation, reconciling their connection to a sound with their detachment from the culture and circumstances that gave it life.

- PHOTO BY MATT BURKHARTT

- Ron Stackman, performing with The Majestics at Three Heads Brewing in 2021.

Stackman knows it ain’t happening perhaps better than anyone. He’s been at it for almost 50 years.

BAHAMA MAMA AND THE BIRTH OF ROCHESTER REGGAE

By all accounts, the Rochester reggae scene began in 1973 when Stackman and two other members of The Majestics — bassist Jim Schwarz and drummer Lou LaVilla — formed Bahama Mama with musician Jim Kraut.

Bahama Mama was an all-white band with roots in rock ‘n’ roll and an admiration for Jamaican music. But it quickly established itself as a serious touring act, playing frequently in New York City and throughout the northeastern United States.

The band solidified its stature as godfather of the genre in upstate New York during a gig in Newport, Rhode Island, when it crossed paths with the late Mike Cacia, a Rochester native who was championing the emerging reggae scene in Boston.

A graduate of The Aquinas Institute of Rochester, Cacia was a prominent concert promoter whose reggae music label, Heartbeat Records, and “Rockers TV” cable show were instrumental in introducing American audiences to reggae. Cacia also managed the influential Jamaican band Toots and the Maytals — whose 1968 single “Do the Reggay” was thought to be the first popular song to use the word “reggae” — and later arranged for Bahama Mama to play with them.

In those days, the relationship between Jamaican reggae artists and bands such as Bahama Mama could be symbiotic. American groups got the opportunity to open for talented reggae musicians who lacked the necessary equipment for touring in the United States, and, in return, doubled as their roadies, supplying gear for each show.

By the end of the decade, Bahama Mama had broken up, and in 1981, its core trio of Stackman, Schwarz, and LaVilla formed The Majestics. It would be a very big year for the band.

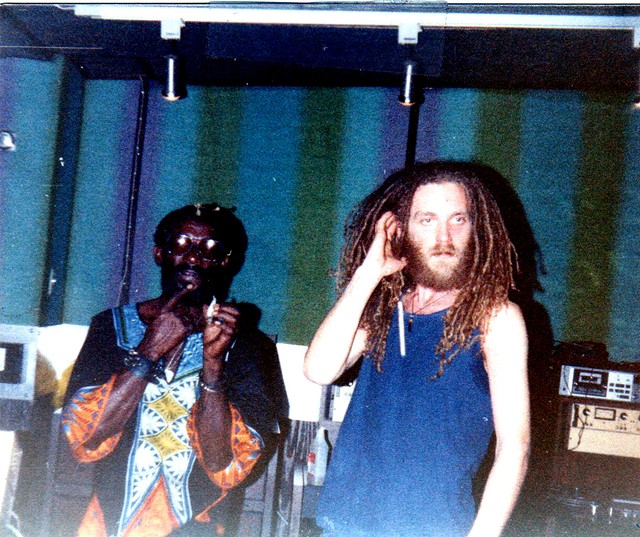

- PHOTO PROVIDED

- Legendary reggae musician Lee "Scratch" Perry, left, and Ron Stackman, of the Majestics, during a recording session in Jamaica for the album "Mystic Miracle Star" in 1981.

He also brought them to Jamaica, where they wrote and recorded the album “Mystic Miracle Star” during a week of overnight sessions. Stackman recalls how Perry holding his harmonica out the car window in Kingston on a drive home from the studio inspired the album’s final track, “Music Breeze.”

Although The Majestics’s collaboration with Perry burnished their reggae credentials and they were generally well received by Rochester audiences, they sometimes met with resistance on the road from promoters and critics who doubted the band’s authenticity.

Once, while the band was touring with the Jamaican singer-songwriter Burning Spear, the concert promoters for a stop at Howard University, an historically Black college in Washington, D.C., were surprised to learn The Majestics were white. The band was paid to not play that night.

A critic who reviewed a show in Burlington, Vermont, described the band’s set as “thankfully short” and its music as a mix of Journey and Toots and the Maytals.

Despite still being booked for shows, including one in December at Three Heads Brewing, in front of a largely white audience, Stackman isn’t convinced The Majestics ever achieved “authenticity” in the genre.

“I really got to say in all honesty, I don't know if we ever really got there as far as that goes,” Stackman says. “I mean, it's always been a little twisted with us. It’s never really been authentic. I mean, it's always been derivative, our style of reggae.”

‘SUFFERERS’ MUSIC’

Reggae emerged in the late 1960s, drawing from Jamaican styles of ska, rocksteady, and mento, a folk music originating in the era of slavery on the island, as well as American R&B and jazz.

The sound is closely linked to Rastafari, a religion in the country that promoted pan-Africanism. While Jamaica had gained independence from England in 1962, the arrival of Rastafarian deity and Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie I in Jamaica in 1966 galvanized the Rastafari-reggae connection that drove the music into the 1970s.

In essence, roots reggae helped articulate Jamaica’s burgeoning cultural, political, and spiritual identity as a decolonized Black nation with strong African roots. In the midst of poverty and violence in the post-independence years, reggae was a means of rising above past and present oppression of Black people at home and abroad.

Formative Jamaican reggae artists such as Bob Marley, Burning Spear, and Jimmy Cliff reflected the voice of the people. Their music was about suffering and political strife, but also delivered a message of love and unity for everyone, regardless of race.

- PHOTO BY JACOB WALSH

- A poster of reggae icon Bob Marley hangs on the wall as Ronnie "Skill" Gordon rehearses with Ignite Reggae Band.

“The haves play the music different because they’re not playing it as sufferers,” he says. “They’re playing it as, ‘I like that!’ See what I’m saying? So it makes the music express differently. Whereas the sufferers are playing it as in, ‘We need to make something happen, we need to eat.’”

- PHOTO BY MATT BURKHARTT

- For Ronnie “Skill” Gordon, the leader of Ignite Reggae Band, the sound of white reggae musicians and Black and Jamaican reggae musicians reflects the difference between haves and have-nots. “The haves play the music different because they’re not playing it as sufferers,” he says.

- PHOTO PROVIDED

- Confrontation was the first Rochester reggae band consisting predominantly of Jamaican musicians.

Tensions in Positive Crisis surfaced, however, when Skill began to question the commitment of the band’s white members to reggae. His concerns over stylistic incompatibility were interpreted as racially bigoted, he says, and the band broke up.

Muskopf and McKenzie went on to form the multiracial band Noble Vibes in 2011, and Skill created the original lineup of Ignite with Jamaican and American Black musicians. Ignite’s current roster includes Black and white musicians.

Both Skill and Muskopf say their differences over Positive Crisis have been put to rest. Still, Muskopf says divisions in the local reggae scene today are due in part to racial differences.

“People want to see people who look like them,” he says.

- PHOTO PROVIDED

- The crowd takes in the live music at Rochester’s cultural Caribbean festival, Carifest, 2017.

“The people that think the reggae stopped (after Marley) — not to pick on them, generally the jam-band guys — will kind of take the reggae and a couple Grateful Dead tunes and kind of mix it, and try to rebrand it as reggae without actually always going to the source,” Muskopf says.

- PHOTO BY JACOB WALSH

- Jason Muskopf, of the multiracial band Noble Vibes, says divisions in the local reggae scene are due in part to racial differences. "People want to see people who look like them," he says.

“You have to know why you’re playing it and who you’re playing to, and why certain things are important,” he says.

EMULATION VS. INSPIRATION

It’s not as though predominantly white reggae bands in Rochester are unaware of their privilege, however.

“We didn’t grow up in Jamaica, so it’s kind of hard for us to understand their struggles,” says Joe Kaplan of Personal Blend and The Forest Dwellers.

For his Forest Dwellers bandmate Anthony DeCausemaker, the band’s legitimacy boils down to the authenticity of its members.

“We're not necessarily trying to emulate something,” DeCausemaker says. “We're being heavily influenced by something, and we're just trying to pay respects.”

- PHOTO PROVIDED

- “We didn’t grow up in Jamaica, so it’s kind of hard for us to understand their struggles,” says Joe Kaplan, left, of The Forest Dwellers.

“I’m not from Jamaica, so I’m trying to mimic,” he says. “I’m trying to learn the songs from the culture, from the literature.”

Luk’s bandmate and fellow guitarist Michael Corey, whose mother is Jamaican, prefers to call their band’s music “reggae-inspired” or “international reggae.” The band’s singer, Yao “Cha Cha” Foli grew up in Ghana.

“Even as a Jamaican, I feel kind of strange sometimes portraying what we do as really this product of a culture that we’re not really from,” Corey says. “But I feel most comfortable when we kind of lean into our backgrounds. We’re from all these different places around the world.”

- PHOTO BY AARON WINTERS

- Mosaic Foundation performs at Three Heads Brewing in 2018.

Corey sees the segregation between white and Black reggae music in Rochester as real. But, he says, the segregation is not exclusive to reggae and has a lot to do with concert venues and which clubs book which acts.

“It's kind of a white male-dominated space, in terms of who's owning these places, who's booking these places,” he says. “So I think that already has a built-in issue with who wants to go play where, who wants to go see shows where.”

Geoff Dale, a co-owner of Three Heads Brewing who regularly books reggae bands there, has seen the homogeneity firsthand.

He acknowledges that bookers play a role in it, but added that some of the segregation stems from a band’s fan base.

“Their fan bases start with their friends, and it sort of grows from there,” he says. “So if you have an all-white band, it tends to make sense that they’re going to have a predominantly white crowd. It’s an unfortunate reality of the world we live in. Just like if you have a predominantly Black reggae band, you're going to have a lot more Black people in the crowd.”

Dale says creating a more inclusive venue requires vigilance and a concerted effort to book Black musicians. Prior to the pandemic, Three Heads had taken strides toward more diverse concert programming, with two month-long concert series featuring local Black artists Avis Reese and Zahyia Rolle.

“I can do a better job about being aware of what I’m booking, and have to be constantly self-evaluating,” he says. “If you start to put a little bit of the work in, the walls start to come down.”

CORRECTION: A previous version of article incorrectly stated the year that Noble Vibes was founded and the year it began its weekly concerts at Milestones. This article has been updated to reflect this change.

Daniel J. Kushner is CITY’s arts editor. He can be reached at [email protected].