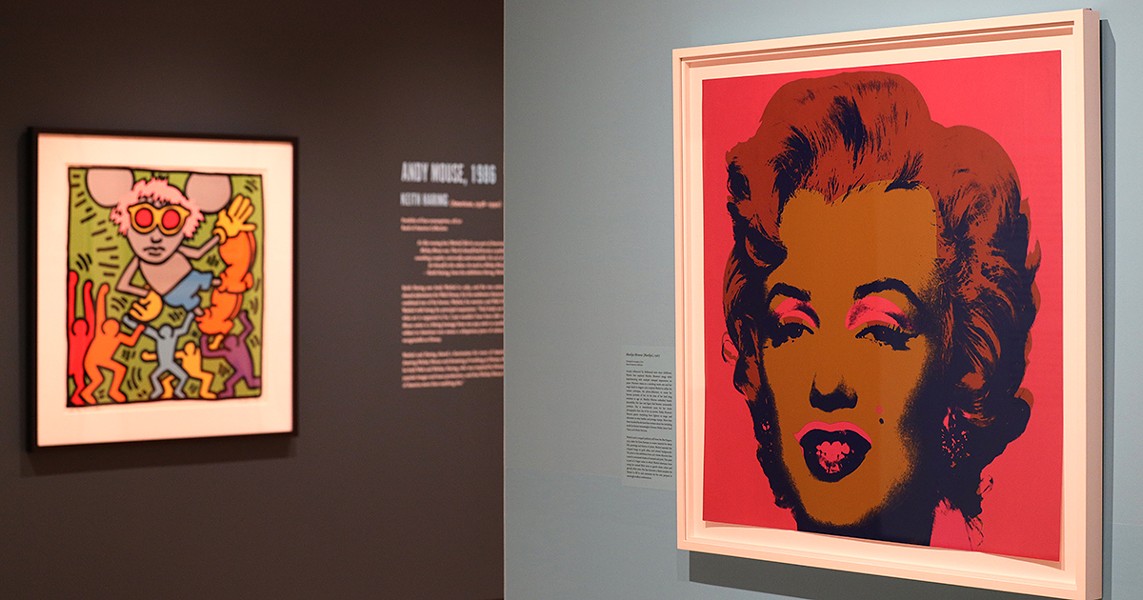

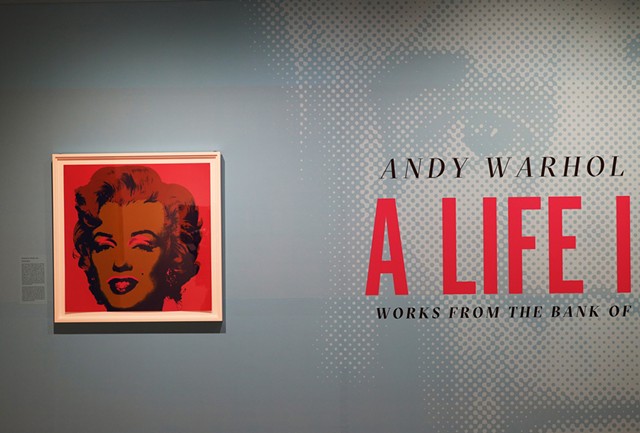

“Season of Warhol,” the newest exhibit at Rochester’s Memorial Art Gallery, is a major event for the city’s art scene that explores Andy Warhol’s wild ride. On display are samples of his vibrant pop art, tributes to his fascination with film and television, and goofy cow wallpaper juxtaposed with an image of the electric chair used to execute Julius and Ethel Rosenberg.

To the museum’s director, Jonathan Binstock, the pop artist was “probably the most influential artist of the 20th century, and probably the most prolific artist of all time.”

Two grand statements. And here’s another: With his signature celebrity portraits — like a saucy Marilyn Monroe exploding in color — Warhol was probably the most celebrity-conscious artist of all time.

Which is what makes the story of Warhol’s camaraderie and would-collaboration with Armand Schaubroeck, a co-owner of Rochester’s iconic House of Guitars, so intriguing.

“He helped me,” Schaubroeck says, “and I was nobody.”

Schaubroeck wasn’t a celebrity when he caught Warhol’s attention in 1966. He was just a guy fresh out of prison who ran a small music store in Irondequoit with his brothers and recorded songs with them in their mother’s basement about his time in the clink under the band name Armand Schaubroeck Steals.

He was a former thief who at 17 was sentenced to three years in juvenile detention at Elmira Correctional Facility, where he was Inmate No. 24145. With that pedigree, Schaubroeck could have been easily overlooked by a celebrity artist who was simultaneously upending traditional art with his Campbell’s soup cans and sucking artists, writers, musicians, and celebrities into his social orbit.

But Schaubroeck wasn’t overlooked, not even when he cold-called Warhol that year at the New York City apartment the artist shared with his mother.

But Schaubroeck wasn’t overlooked, not even when he cold-called Warhol that year at the New York City apartment the artist shared with his mother.

“He goes, ‘How’d you get this number?’” Schaubroeck recalled. “And I said, ‘I called the Rundel Library.’ And he goes, ‘What’s Rundel?’ I said, ‘Oh, it’s just a big library in Rochester, New York. And I had them look it up in “Who’s Who.”’ And he goes, ‘My number’s in there?’ And he laughed.”

“Season of Warhol” introduces Rochester to Warhol’s prints and films and “Silver Clouds,” an airy representation of the silver interiors of Warhol’s famous studios, The Factory. Silver balloons, filled with helium or air, adrift.

“You can kind of control them for a moment,” Binstock says of the balloons, “but then they’re doing their own thing, like this is the spirit of The Factory, this is the energy of The Factory. Let people come together and, like, see what happens. It’s just” — and here he channels Warhol — “‘Turn on the film camera, we don’t have a script, but you put on a cowboy hat and you take off your clothes, and let the screenplay happen in front of the lens of the camera, I’m going into the other room, I have to make some calls . . .’”

Or take some calls, as he did that day in 1966 when Schaubroeck caught him unawares at home.

After Warhol got a chuckle out of Schaubroeck’s ingenuity in tracking him down, Schaubroeck recalled, “I talked about my jail thing, and how I was working on prison songs and stuff, and he got very interested in it. He asked me to send him a tape and I did. . . . Then he started calling me to come to The Factory right away.”

After Warhol got a chuckle out of Schaubroeck’s ingenuity in tracking him down, Schaubroeck recalled, “I talked about my jail thing, and how I was working on prison songs and stuff, and he got very interested in it. He asked me to send him a tape and I did. . . . Then he started calling me to come to The Factory right away.”

As Schaubroeck and others familiar with his relationship with Warhol recall, Warhol was struck by the concept of Armand Schaubroeck Steals — juvenile delinquency as a musical persona was counterculture-cool, a standard for which Warhol was by then a standard bearer.

So Schaubroeck showed up at The Factory with his brothers, Bruce, who played drums in the band, and Blaine, who played bass, and three hours of tapes — songs, lyrics, and spoken material about prison life as a youngster.

Young boy / the way he walks / the way he holds his cigarette / he reminds me of my wife at night.

But as the two men tried to grow the jail culture of “Armand Schaubroeck Steals” into a pop-culture touring musical, logistical issues became evident. Mainly the band, which consisted of the Schaubroeck brothers and a few Irondequoit friends.

“Everybody that was in it worked at the House of Guitars, and back then we only had one or two employees, and they were in the band,” Schaubroeck says. “And he wanted us to sign up for seven days a week for three years. The problem is we’d lose House of Guitars, and I didn’t ever want to do that, so I was trying to talk him into doing a movie.”

As the story goes, if it weren’t for perhaps the most infamous artist assassination attempt ever, Warhol might have turned the concept of “Armand Schaubroeck Steals” into a very unconventional musical — maybe even a movie — based on the band’s songs and their spoken-word intros.

But the question was settled in 1968, when Warhol was shot by Valerie Solanas, a paranoid schizophrenic hanger-on at The Factory. Warhol was seriously wounded, and declared dead at one point. He lived. But his vision for “Armand Schaubroeck Steals” died.

But the question was settled in 1968, when Warhol was shot by Valerie Solanas, a paranoid schizophrenic hanger-on at The Factory. Warhol was seriously wounded, and declared dead at one point. He lived. But his vision for “Armand Schaubroeck Steals” died.

“I’d been sitting on it since the ’60s,” Schaubroeck says. “Also, John Hammond at Columbia Records was very interested in it. Andy would always call him, ‘your Hammond.’ ‘Tell your Hammond this,’ almost like he had a little resentment about it. ‘Tell your Hammond that he can pay for the whole play for soundtrack rights.’ And I said, ‘You really want me to say that, Andy?’ He goes, ‘Yes.’ So I went up over.

“He liked the jail thing too. And I was kind of proud of that because he’s the guy that signed Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen.”

While Warhol was hospitalized, Schaubroeck re-recorded the music and released it as a three-LP collection, “A Lot of People Would Like to See Armand Schaubroeck . . . DEAD.” The cover was a photo of Schaubroeck with a fake bullet hole in his forehead, blood running down his face.

“Once I put it out on my own,” Schaubroeck says, “it kinda killed that because he doesn’t want to look like, he didn’t say it, I don’t think he wanted to look like he picked up something else that was out already.”

The collaboration was finished, but Schaubroeck would still hang around The Factory from time to time. Warhol used to call the shop. “They’d page me, ‘Andy Warhol on the phone,’ and stare at me, you know,” Schaubroeck said.

He knew Warhol well enough that, when a local television news program reported on Warhol speaking at Rochester Institute of Technology in 1967, Schaubroeck recognized that the guy in heavy pancake makeup, black-framed eyeglasses and floppy hair painted silver and white wasn’t Warhol. It was an actor who had appeared in a few Warhol films, and paid by Warhol to impersonate him on the college tour. After a few more speaking engagements, someone at the University of Utah who knew the real Warhol pointed out the hoax.

“He said that he thought the actor made a better Andy than he would ever make,” Schaubroeck recalled Warhol saying when he asked him about it later.

“He liked to go to parties, and I would never go to parties with him, trying to keep it business,” Schaubroeck. “And I misunderstood, because every night he’d leave maybe about six o’clock or so from The Factory, and parties would go on all night at The Factory. I mean music blasting, bands playing and people sleeping there and drugs, sex, you name it was going on there all over the place. And he’d leave and not worry about it.”

But it wasn’t all play and no work.

“This idea that he didn’t care,” Binstock says, “and that he just transparently, thoughtlessly collected stuff or made stuff or talked about stuff, is what he would want you to believe. Because that was a strategy for getting the attention of the general public, and also the serious art public.”

But he didn’t want you to know that. The contrarian draws attention. Binstock reads a quote — a confession, actually — from Warhol himself:

“If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.”

“Now you have to think about a statement like that in an art world that really takes itself very seriously,” Binstock says. “And here comes a guy that says, ‘I don’t know, it’s really, there’s nothing to it, I’m just doing these things because I have nothing better to do with my time.’”  The sheer volume of creativity disputes that notion. “Warhol was a workaholic,” Binstock says. “He took speed every day for at least a decade or more, he worked all the time.”

The sheer volume of creativity disputes that notion. “Warhol was a workaholic,” Binstock says. “He took speed every day for at least a decade or more, he worked all the time.”

Warhol died 33 years ago, at age 58, of complications following gallbladder surgery.

Fast forward to May 2013, and three employees of the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh are conducting an autopsy of sorts before a small audience. They are not examining a body, but a body of work — a plain cardboard box that is one 610 that Warhol had packed with the detritus of American society he had collected over the years. He called them Time Capsules. This one was dated 1978.

One by one, the employees carefully removed its contents. Among the dozens of items were paper McDonald’s take-out bags, clearly used. A cook book. A card that read “Flowers are sex organs.” An unsmoked cigar. A telegram concerning a possible meeting with Mick Jagger.

And a vinyl record that drew laughter from the spectators. The title was “Ratfucker,” the final album by Armand Schaubroeck Steals.

Jeff Spevak is WXXI’s Arts & Life editor and reporter. He can be reached at [email protected].

To the museum’s director, Jonathan Binstock, the pop artist was “probably the most influential artist of the 20th century, and probably the most prolific artist of all time.”

Two grand statements. And here’s another: With his signature celebrity portraits — like a saucy Marilyn Monroe exploding in color — Warhol was probably the most celebrity-conscious artist of all time.

Which is what makes the story of Warhol’s camaraderie and would-collaboration with Armand Schaubroeck, a co-owner of Rochester’s iconic House of Guitars, so intriguing.

“He helped me,” Schaubroeck says, “and I was nobody.”

Schaubroeck wasn’t a celebrity when he caught Warhol’s attention in 1966. He was just a guy fresh out of prison who ran a small music store in Irondequoit with his brothers and recorded songs with them in their mother’s basement about his time in the clink under the band name Armand Schaubroeck Steals.

He was a former thief who at 17 was sentenced to three years in juvenile detention at Elmira Correctional Facility, where he was Inmate No. 24145. With that pedigree, Schaubroeck could have been easily overlooked by a celebrity artist who was simultaneously upending traditional art with his Campbell’s soup cans and sucking artists, writers, musicians, and celebrities into his social orbit.

- PHOTO BY MAX SCHULTE

- Armand Schaubroeck, co-owner of the House of Guitars and a former rock artist, displays the album he cut in 1968, "A Lot of People Would Like to See Armand Schaubroeck . . . DEAD."

“He goes, ‘How’d you get this number?’” Schaubroeck recalled. “And I said, ‘I called the Rundel Library.’ And he goes, ‘What’s Rundel?’ I said, ‘Oh, it’s just a big library in Rochester, New York. And I had them look it up in “Who’s Who.”’ And he goes, ‘My number’s in there?’ And he laughed.”

“Season of Warhol” introduces Rochester to Warhol’s prints and films and “Silver Clouds,” an airy representation of the silver interiors of Warhol’s famous studios, The Factory. Silver balloons, filled with helium or air, adrift.

“You can kind of control them for a moment,” Binstock says of the balloons, “but then they’re doing their own thing, like this is the spirit of The Factory, this is the energy of The Factory. Let people come together and, like, see what happens. It’s just” — and here he channels Warhol — “‘Turn on the film camera, we don’t have a script, but you put on a cowboy hat and you take off your clothes, and let the screenplay happen in front of the lens of the camera, I’m going into the other room, I have to make some calls . . .’”

Or take some calls, as he did that day in 1966 when Schaubroeck caught him unawares at home.

- PHOTO BY MAX SCHULTE

- Workers at the Memorial Art Gallery prepare the "Season of Warhol" exhibit.

As Schaubroeck and others familiar with his relationship with Warhol recall, Warhol was struck by the concept of Armand Schaubroeck Steals — juvenile delinquency as a musical persona was counterculture-cool, a standard for which Warhol was by then a standard bearer.

So Schaubroeck showed up at The Factory with his brothers, Bruce, who played drums in the band, and Blaine, who played bass, and three hours of tapes — songs, lyrics, and spoken material about prison life as a youngster.

Young boy / the way he walks / the way he holds his cigarette / he reminds me of my wife at night.

But as the two men tried to grow the jail culture of “Armand Schaubroeck Steals” into a pop-culture touring musical, logistical issues became evident. Mainly the band, which consisted of the Schaubroeck brothers and a few Irondequoit friends.

“Everybody that was in it worked at the House of Guitars, and back then we only had one or two employees, and they were in the band,” Schaubroeck says. “And he wanted us to sign up for seven days a week for three years. The problem is we’d lose House of Guitars, and I didn’t ever want to do that, so I was trying to talk him into doing a movie.”

As the story goes, if it weren’t for perhaps the most infamous artist assassination attempt ever, Warhol might have turned the concept of “Armand Schaubroeck Steals” into a very unconventional musical — maybe even a movie — based on the band’s songs and their spoken-word intros.

- PHOTO BY MAX SCHULTE

- Workers at the Memorial Art Gallery hang cow wallpaper that is part of the "Season of Warhol" exhibit.

“I’d been sitting on it since the ’60s,” Schaubroeck says. “Also, John Hammond at Columbia Records was very interested in it. Andy would always call him, ‘your Hammond.’ ‘Tell your Hammond this,’ almost like he had a little resentment about it. ‘Tell your Hammond that he can pay for the whole play for soundtrack rights.’ And I said, ‘You really want me to say that, Andy?’ He goes, ‘Yes.’ So I went up over.

“He liked the jail thing too. And I was kind of proud of that because he’s the guy that signed Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen.”

While Warhol was hospitalized, Schaubroeck re-recorded the music and released it as a three-LP collection, “A Lot of People Would Like to See Armand Schaubroeck . . . DEAD.” The cover was a photo of Schaubroeck with a fake bullet hole in his forehead, blood running down his face.

“Once I put it out on my own,” Schaubroeck says, “it kinda killed that because he doesn’t want to look like, he didn’t say it, I don’t think he wanted to look like he picked up something else that was out already.”

The collaboration was finished, but Schaubroeck would still hang around The Factory from time to time. Warhol used to call the shop. “They’d page me, ‘Andy Warhol on the phone,’ and stare at me, you know,” Schaubroeck said.

He knew Warhol well enough that, when a local television news program reported on Warhol speaking at Rochester Institute of Technology in 1967, Schaubroeck recognized that the guy in heavy pancake makeup, black-framed eyeglasses and floppy hair painted silver and white wasn’t Warhol. It was an actor who had appeared in a few Warhol films, and paid by Warhol to impersonate him on the college tour. After a few more speaking engagements, someone at the University of Utah who knew the real Warhol pointed out the hoax.

“He said that he thought the actor made a better Andy than he would ever make,” Schaubroeck recalled Warhol saying when he asked him about it later.

“He liked to go to parties, and I would never go to parties with him, trying to keep it business,” Schaubroeck. “And I misunderstood, because every night he’d leave maybe about six o’clock or so from The Factory, and parties would go on all night at The Factory. I mean music blasting, bands playing and people sleeping there and drugs, sex, you name it was going on there all over the place. And he’d leave and not worry about it.”

But it wasn’t all play and no work.

“This idea that he didn’t care,” Binstock says, “and that he just transparently, thoughtlessly collected stuff or made stuff or talked about stuff, is what he would want you to believe. Because that was a strategy for getting the attention of the general public, and also the serious art public.”

But he didn’t want you to know that. The contrarian draws attention. Binstock reads a quote — a confession, actually — from Warhol himself:

“If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.”

“Now you have to think about a statement like that in an art world that really takes itself very seriously,” Binstock says. “And here comes a guy that says, ‘I don’t know, it’s really, there’s nothing to it, I’m just doing these things because I have nothing better to do with my time.’”

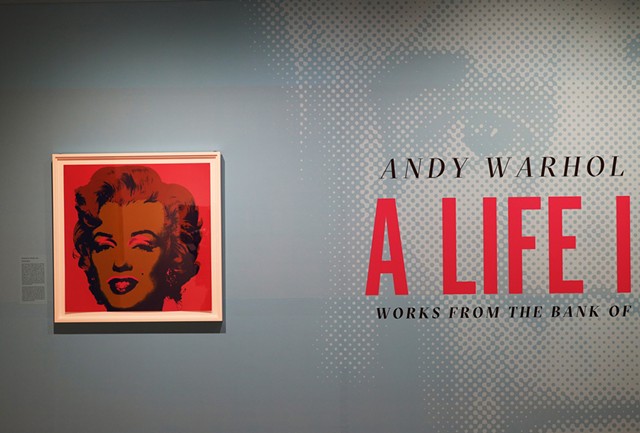

- PHOTO BY MAX SCHULTE

- "Season of Warhol" is on display at Rochester's Memorial Art Gallery through March.

Warhol died 33 years ago, at age 58, of complications following gallbladder surgery.

Fast forward to May 2013, and three employees of the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh are conducting an autopsy of sorts before a small audience. They are not examining a body, but a body of work — a plain cardboard box that is one 610 that Warhol had packed with the detritus of American society he had collected over the years. He called them Time Capsules. This one was dated 1978.

One by one, the employees carefully removed its contents. Among the dozens of items were paper McDonald’s take-out bags, clearly used. A cook book. A card that read “Flowers are sex organs.” An unsmoked cigar. A telegram concerning a possible meeting with Mick Jagger.

And a vinyl record that drew laughter from the spectators. The title was “Ratfucker,” the final album by Armand Schaubroeck Steals.

Jeff Spevak is WXXI’s Arts & Life editor and reporter. He can be reached at [email protected].