W. Michelle Harris is a digital-media artist who is tackling social and political issues by using racist historic imagery, self-portraiture, and audience interaction. She frequently collaborates with the Rochester repertory dance company BIODANCE, complementing the choreography with breathtaking media installations. And she's an associate professor in RIT's School of Interactive Games and Media — a black woman thriving in a field that is still dominated by white men.

Much of Harris's current work focuses on issues facing the black community, using the most contemporary of artistic expression to comment on problems black people and women have faced for centuries.

- PHOTO PROVIDED

Her 19-minute film "Flawless Ladies" is a love letter to black women, shining a spotlight on their contributions to human advancement and culture. The kaleidoscopic wonder features digitally manipulated pictures of famous, obscure, and anonymous black women scientists, artists, musicians, writers, activists, and athletes. And she pairs them with inspiring songs that often contain social messages, works by Danielle Ponder & The Tomorrow People, Nina Simone, Rosetta Tharpe, Sharon Jones, and others.

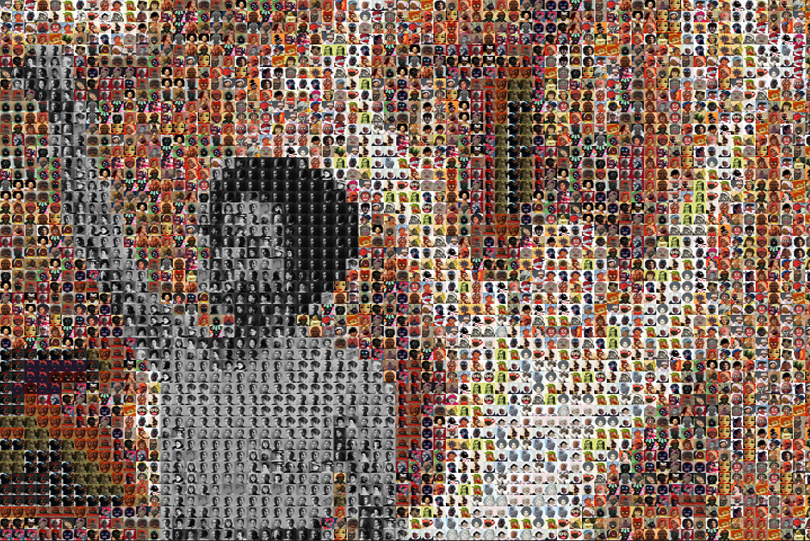

Harris's "Can't/Breathe Mirror" is an interactive photographic mosaic work that she created as a memorial to black people who have been killed by the police. Projected on a wall, the piece is a grid of nearly 200 pictures of black men and women, elders and children.

In front of the wall is an altar holding candles and a camera pointed out toward viewers, capturing their forms and "mirroring" them onto the grid of faces. The result is a rolling darkness that moves over the portraits as the viewers move. It's a daunting experience to watch your own shadow fall over the sea of smiling faces.

(Harris's goal was to find images of the victims smiling, where they were alive and happy, but it wasn't always easy.)

Her practice, she says, has been to update the work when more people are killed, but she hasn't done that since August of 2017, so there are people who haven't yet been represented in the piece. She began working on it in July of 2014, when Eric Garner was killed. (The title comes from Garner's dying plea to the officer who had him in a chokehold). The set of people begins with Fred Hampton, who was shot by police in 1969 while he was sleeping next to his pregnant fiancée.

When Harris showed the work at a conference in Rochester, an attendee walked by the installation, stopped and came back, looked at Harris, and said, "I know him," gesturing to the picture of Prince Jones Jr., who, she explained, was a fellow student when she attended Howard University. He was shot in 2000 after police followed him for 16 miles, allegedly believing that the car he was driving was linked to a stolen weapon.

The work doesn't include every black person killed by police, and the selection isn't a scientific process, Harris says. "If you look for records of people who were unarmed, that gives you one number. And if you look for records where they didn't have a gun, they had something else. Then you have the kid from St. Louis who had the butter knife; he's in here; he wasn't really armed. And people just defending themselves in their home, I included them, too."

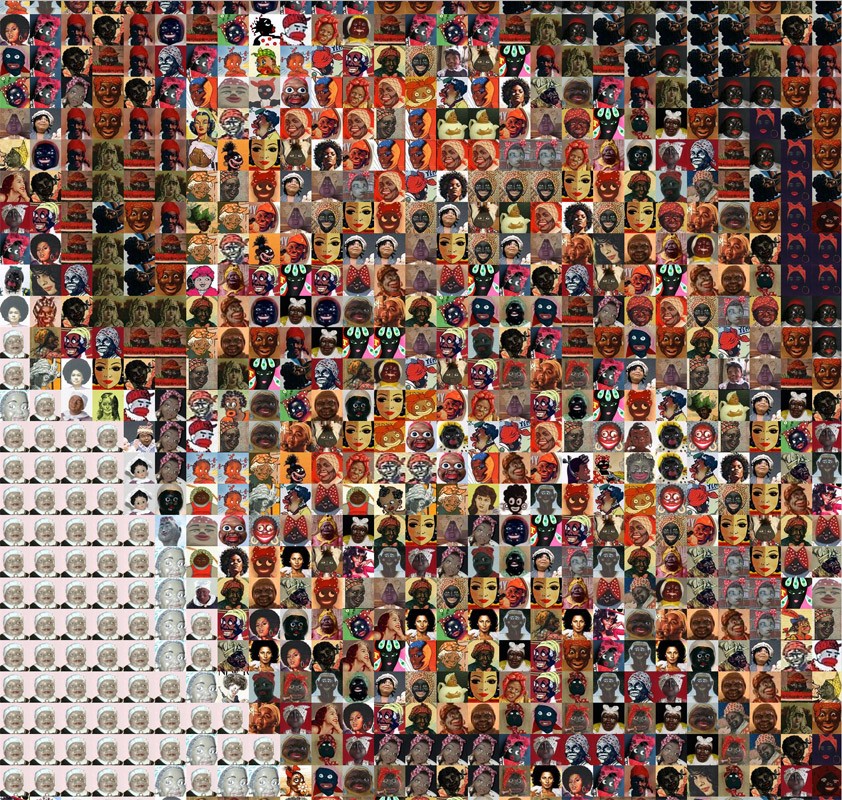

One of Harris's particularly compelling works is "Mammy's Revenge," a photographic mosaic using thousands of little images of stereotypes of black women, from old advertising ephemera that portrayed Jezebel and Mammy figures to the 2008 cover of The New Yorker that depicts Michelle Obama as a terrorist. When you step back from the image, the individual images coalesce into a powerful portrait of a smiling, confident Harris.

To create these works, Harris uses a Mac Book Pro and software that replaces pixels with images. The result is not unlike looking at a Chuck Close portrait, except that the tiny squares aren't abstract color swirls, but politically charged images.

Harris didn't originally set out to be an artist, or to be teaching college courses in 2D animation, interaction design, and programming. But art, tech, games, and teaching are in her roots. Both of her folks were math majors at Virginia State University and were active members of the National Technical Association while Harris was growing up, and her father organized tech enrichment outings for black high school students, including Harris and her sister. At home the family had an Apple 2 computer, played "Helicopter Rescue," and learned some BASIC programming languages, she says.

Her mother became a teacher and was handy with sewing, crocheting, and macramé, and her father specialized in using computers to support aviation science. He went on to manage supercomputers for NASA, and lobbied Congress to fund supercomputers at NASA and partner universities.

Harris says her "high school logic" went as follows: "I like computers. I am good at subjects that are core for engineers, and I knew engineers thanks to NTA. Carnegie Melon University is Number 1 in computer engineering. I don't know if I could continually come up with enough ideas to be an architect."

She earned an undergraduate degree in computer engineering from Carnegie Melon. There she discovered human-computer interaction as a field, where the focus was "programming computers to help people do things well," she says.

But she realized that "making chips go fast, with a roomful of white guys who loved making chips go fast" was not her scene. "I was like: 'I don't care about making the thing go faster. I care about the interaction between the people and whatever they're using the software for.'"

After a brief but unfinished stint in graduate school, she landed a job doing interactive design at Pacific Northwestern National Laboratory in Richland, Washington.

"While I was there, the internet happened," she says. "Interactive CD's happened. Things like that. So I got to do beginnings of things like that as they were developing. And eventually, I was there long enough, you were at the level where you get promoted and manage people. I didn't want to manage people. And also at that point I was not really captivated by the projects I was working on. I ended up taking an art class before work. And getting into a band and community theater and doing stuff after work."

She sang with a blues, funk, and rock band called Six-legged Frog, an allusion to the nearby Hanford nuclear waste site. "There are actual VHS tapes around somewhere," she says, laughing.

Harris's parents thought that her artistic curve in her 20's was "cute, then risky," she says, after she left her solid PNNL job and sold her house to move to New York City, but they helped her every step of the way.

- PHOTO PROVIDED

"I didn't want to manage software projects, I wanted to keep designing and building software that incorporated new media," she says. "Where design and tech were together. Where the new media development was the center of the business, not the support function, unlike my father's path."

She moved to New York City, "where the stuff I was interested in was the focus at particular companies," she says. "Web agencies were just starting to happen then." She worked as an information architect, applied to graduate school at New York University, and received a full ride. Six months after graduating with a degree from the school's Interactive Telecommunications Program, which mixed art and tech, her mother alerted her to an email from a recruiter at RIT, and she moved to Rochester in 2003 to take the job.

Though Harris says she's seen more women in the tech fields than before, there are still few black people.

"In the early 90's, I interviewed in a place with a lot of older white guys in white short-sleeved oxford shirts," she says. "At PNNL/Battelle, I was recruited by women and worked with mixed-gender groups, even in management — though overwhelmingly white."

- PHOTO PROVIDED

RIT's faculty demographics are better than PNNL's, she says, but she takes note of the demographics of her students — and reminds them to notice it, too — and of the companies hiring them. "Usually there are more puppies in their staff photos than black people," she says. "Usually even the white women are mostly in HR or other support functions."

Harris's newest collaboration with BIODANCE, titled "Loom," will premiere at the company's 12th anniversary celebration May 17 to 19 at Geva Theatre Center's Fielding Stage. Information: biodance.org.