Although the George Eastman Museum recently announced that its entire collection is now viewable online, don't let that stop you from making the trip. A number of fascinating shows now on view provide the casual goer and the history enthusiast alike with enough interest to fill a day. And there are of course the borrowed exhibits tha can only be viewed in person.

In the museum's Project Gallery, Catherine Opie's "700 Nimes Road" is a meditative, candid peek into the private residence and inner life of Elizabeth Taylor. Given free access to document the space as she wished, Opie shot thousands of images over the course of six months, from 2010 to 2011 — Taylor died during this period, in March 2011.

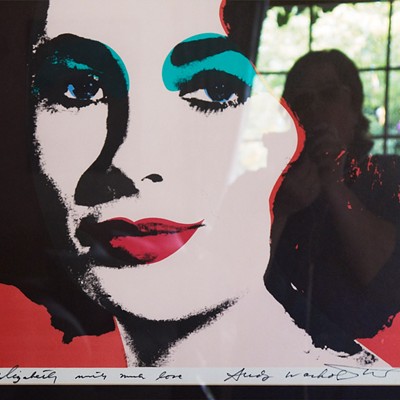

"How can an artist construct a fresh, distinctive portrait of one of the most photographed celebrities in the world?" a bit of wall text in the exhibit inquires. Though the show contains images of Taylor through family photos, and her likeness as depicted in a prized work by Andy Warhol, Opie's focus settles upon the tangible-intangible interplay between the tactile trappings of a life in the limelight and the private self-reflections particular to the star.

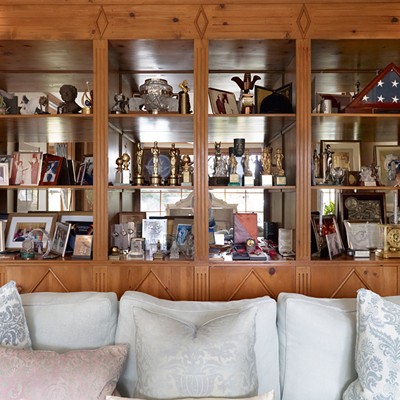

While providing the sum of a renowned life, Opie's images convey also the feeling of a lived-in environment. Taylor's awards are enshrined in muted, slightly rustic rooms, and her associations with other celestial humans, such as Michael Jackson, come down to Earth when framed in mundane snapshots at a bedside table. A grouping of framed family photos includes a card with the same "Footsteps in the Sand" quote you might find on your aunt's fridge.

The portfolio "humanizes Taylor — she was after all a grandmother nearing the end of her life — while maintaining her status as an iconic celebrity who used her staggering beauty and talent to advocate for those in need," writes Helen Molesworth, chief curator at The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, in a provided statement.

Opie captures a heap of jeweled and ordinary AIDS ribbons, representing one of Taylor's specific passions (she co-founded the American Foundation for AIDS Research, and founded the Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation).

Deeper into the gallery, one wall is dedicated to images of Taylor's clothing: rows of shimmering dresses, furs, and leather coats on hangers, presented without fanfare as though the viewer merely opened a wardrobe.

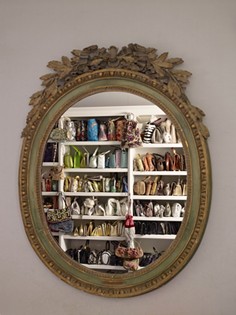

Opie repeats this method of providing teasing slices again and again, at times using mirrors to frame an incomplete view of a whole, and alludes to opulence and abundance without tipping into the cold vulgarity of excess.

At many points, any ravenous curiosity about celebrity is quieted and humbled by Opie's focus on the basic humanity of the woman.

These images "satisfy our curiosity about the private life of one of Hollywood's most enduring legends," Molesworth writes. "However, the photographs do not feel invasive or sensational. Rather, Opie's camera caresses tabletops, knickknacks, and furs like a small child running her hand over appealing surfaces so as to learn them better."

The power of the work comes from a gently exciting push and pull between what is recognizable from Taylor's public life and the glimpses of her private reality — how the accoutrements of her accomplishments and fame were interpreted by the woman herself and incorporated into her environment of memory.

One of the most curious shots in the oeuvre is "The Quest for Japanese Beef," named for the words enigmatically scrawled in lipstick upon a vanity mirror, above neat rows of makeup and the glints of jewels.

In one of the few outdoor shots, Opie showcases "The Elizabeth Taylor Rose" as full, blushing blooms a bit beyond their prime, standing proud and vibrant in a private yard.

Opie again hints at age in "Balloon Shades," an odd shot in which the artist has centered on the embroidered window treatments. The image both echoes Taylor's aesthetic tastes found elsewhere in the show — with muted jewel tones and slight wear and tear to the house, forming a portrait of lived-in elegance. But the "sumptuous fabric possesses bodily qualities: Its sags recall breasts, buttocks, and wrinkled flesh," provided text points out.

As a whole, the show forms an acute portrait of its subject; her presence is felt through her environment and belongings. But perhaps the most accurate portrait of Taylor-the-legend comes in the form of some of the more unique images Opie shot of the star's jewels, which maintains the shifting unknowability of a person amid so many straightforward images of her stuff.

Prismatic octagon glories puncture an ethereal, milky atmosphere in the image, "Yellow Diamond Abstract." To create the shot, Opie brought one piece fromTaylor's jewelry collection outside, "where it caught a refracted the brilliant Southern California sunlight," provided information states. "Refraining from fetishizing Taylor's jewelry for its monetary value, the photograph conveys the sensorial pleasures of diamonds that delighted Taylor."