There's much to be said about the disappearing scientific element of making art and the stalwart enthusiasts keeping it alive. Chemistry and creativity have strolled hand-in-hand throughout human history, but just as the majority of painters stopped grinding their own minerals when they could buy any ready-made hue, most photographers' understanding of chemistry and calculations faded with the onset of digital tech.

But analog vernacular is alive and well in some corners. The current show at the Genesee Center's Community Darkroom Galleries spotlights the darkroom work of three photographers — Chris Holmquist, Jonathan Merritt, and Mark J. Watts. Despite having embraced digital photography, their fondness for older modes of making helps keep those practices alive.

"Under Safelight" draws its title from a bit of old-school photography jargon. It refers to the filtered light that lets photographers see what they are doing in the darkroom, without exposing their work to damaging rays. The title evokes the elusive image of a solitary photographer-scientist tinkering with chemicals, with only a soft red glow pushing at the enveloping shadows.

The smallish, meditative work represented in the show speaks of the romantic apprehension of pursuing an effect, with no guarantee the experiment will yield the desired outcome. It's the difference between knowing how to drive and knowing your engine through and through. No doubt that strictly-digital photographers achieve artfulness, but the thrill of the darkroom is about knowing how to make those effects by hand, and at the expert level, to individualize the formula toward limitless potentials.

- PHOTO PROVIDED

- "The Back, Back Yard (of Nathan Lyons' Old Studio)," a Polaroid Polacolor print by Chris Holmquist.

In his statement, Holmquist points out that "using a darkroom today is a choice, and no longer a necessity as it was for the first 160 years of photography. Nowadays, those who do it have different reasons than image makers of yore, and often those reasons are hard to articulate."

For Holmquist, the pursuit of old processes is as much "about collecting old darkroom paraphernalia as it is about making gorgeous prints on silver-gelatin papers ... and its as much about reading antiquated books or old patents as it is about taking a really great photograph," he says. "Making photographic prints with chemical technology turns out to be a remarkably multidisciplinary affair."

His work, on display in the Sunken Room, varies greatly in subject matter. There are the motion studies of "Pow Wow," a tiny portrait of a Native American dancing, and "The Goat," in which the shaggy bulk of the beast is barely contained within the tight shot. His quiet still life, "A Moment on the Porcelain," depicts the elegant splay of a houseplant catching slanted light on the back of a toilet.

Holmquist shakes up his silver gelatin prints with "The Back, Back Yard (of Nathan Lyons' Old Studio)," a series of five Polaroid Polacolor prints that together form a broken panorama of tangled flora that dwarfs the modest buildings beyond. In its gentle spectrum of hues with colorful rays jetting through the greenery, the work stands out as the most colorful in the show's sea of grayscale images. You can achieve something akin to these dreamy images by using digital filters, but those severely limit the individual nuances you'd be able to get. And by doing it the old school way, you learn how it's done.

Mark J. Watts compares silver gelatin prints made in a darkroom to other analog technologies, such as vinyl records. "Many people say that vinyl records sound 'warmer' compared with digital files, I feel that darkroom prints look 'richer' compared to their digital counterparts," he says.

Here, Watts shows two distinct bodies of work in silver gelatin: "From Water" and "Men with Dogs." The former group includes 11 small studies of environments in flux. His statement says he aims to frame "change brought to the landscape by water, erosion, and time." By shooting not from the shore but from the perspective of the water, looking at banks and bordering buildings, he forms portraits of bodies-in-motion glancing back at damage done.

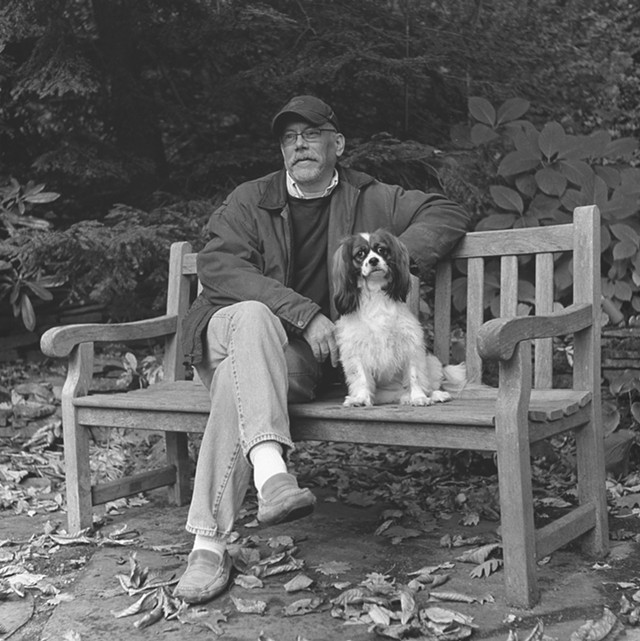

- PHOTO PROVIDED

- "Bella and Mark," a silver gelatin prints from Mark J. Watts's "Men and Dogs" series.

Watts says the impetus for his "Men with Dogs" series is to provide the subjects and their families with an heirloom print. The images strike a balance between formal portrait, focusing on the bond between each pair, and casual in their outdoor settings, with the backdrops of yards, woods, and the backs of houses.

Jonathan Merritt's work is about stripping a specific scene down to a near abstraction, and distilling his momentary apprehension of its essence. He does this by going out to shoot at sleepy hours, when the heaviest presence is atmosphere and the light of streetlamps.

"When you wander the confluence of urban and suburban, it's difficult to notice the details when the world is so loud and busy," Merritt writes in his provided statement. "But at night, it's a different story. With the slow, careful and meditative quality of camera in hand, I explore this territory in that cool, solitary quiet.

- PHOTO PROVIDED

- Jonathan Merritt's "Under Safelight no. 12" focuses on the visual white noise of spaces during quieter hours.

Through his smart cropping of specific plays of light and shadow, familiar settings and objects become slightly surreal. Cracked sidewalks or still black puddles reflecting nearly nothing — white noise on a day-to-day basis — become the subject. Gritty urban corners are cleansed by sharp chiaroscuro, but the graphic quality of this geometric shadow play is wonderfully complicated by the texture of street debris, clouds, or a field of perfect raindrops upon car hoods. Through Merritt's eyes, these scenes feel like fresh, undiscovered territory.